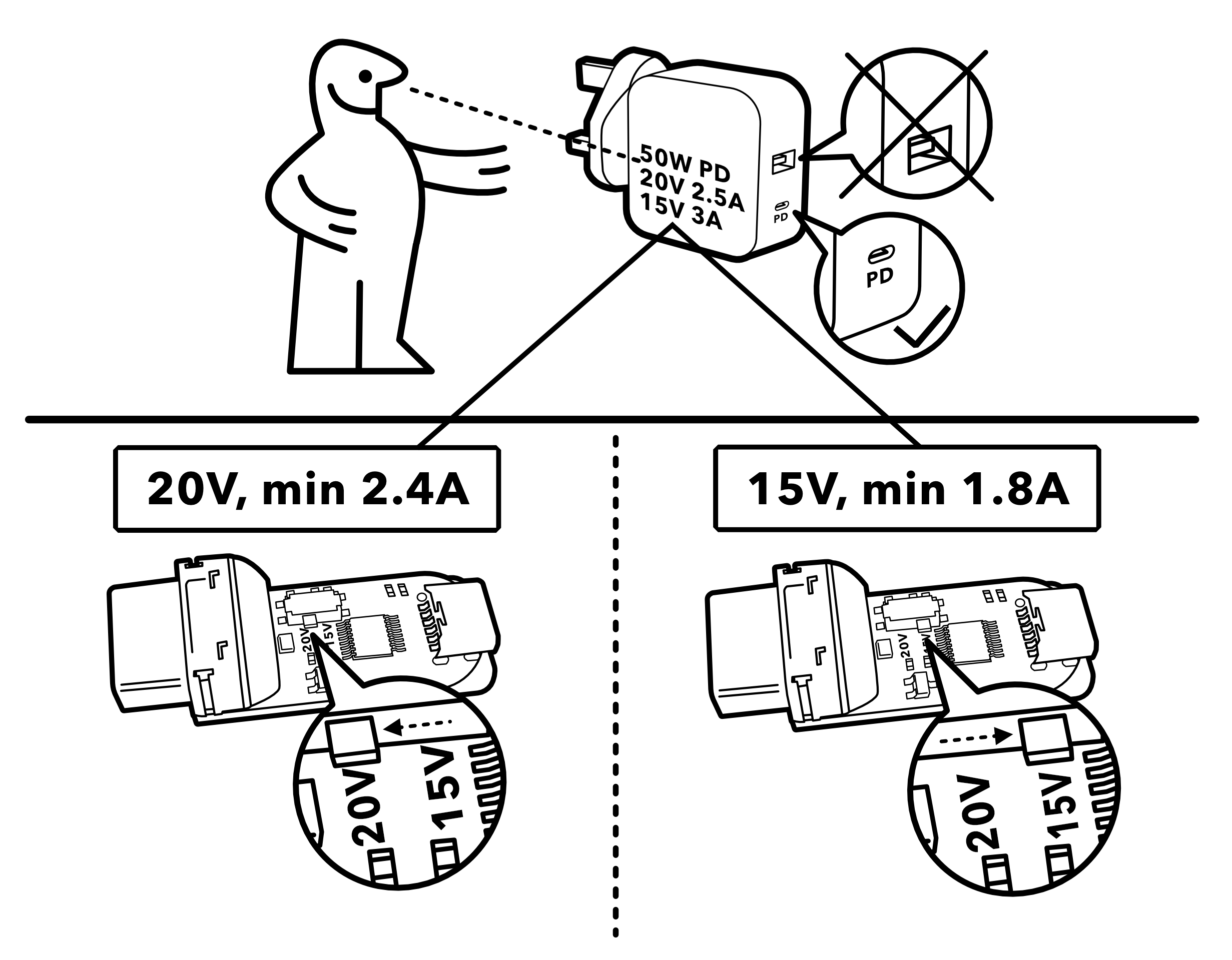

USB-C Power Delivery 3.0 (PD3.0) introduces a new Programmable Power Supply (PPS) mode, which allows a device to negotiate any supply of 3.3-21 V in 20 mV steps, and up to 5 A of current in 50 mA steps. To make use of this new standard, [Ryan Ma] create the PD Micro, an Arduino-compatible development board, and a self-contained software library to allow easy integration of PD3.0 and the older PD2.0 into projects.

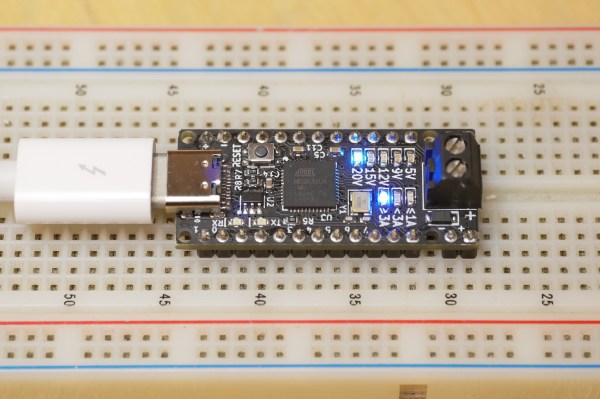

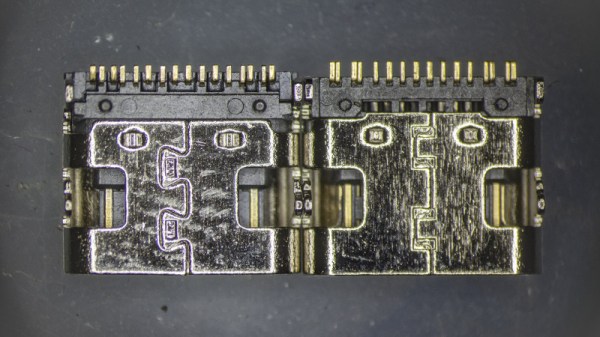

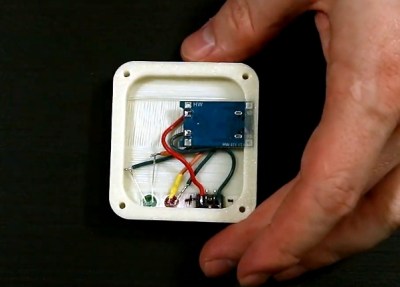

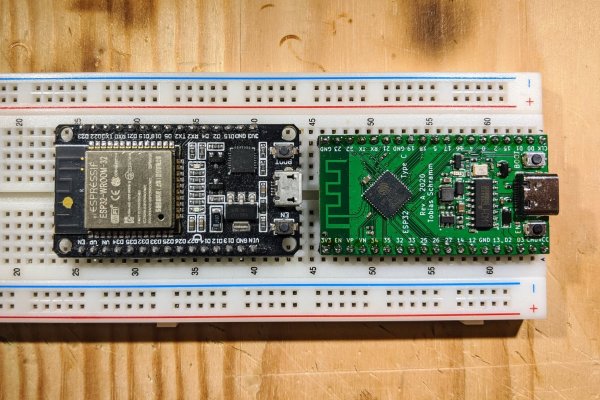

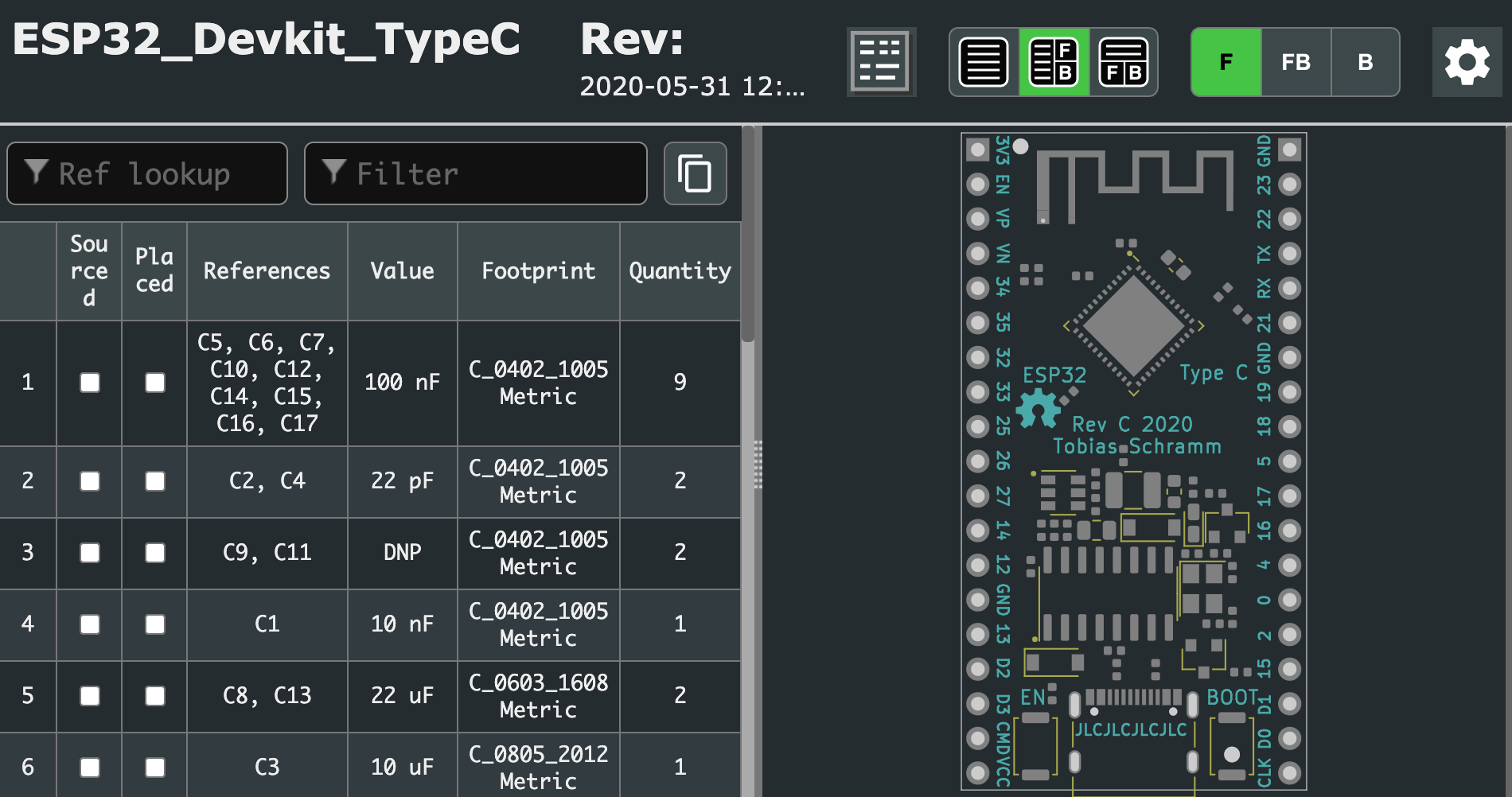

The dev board is built around an ATMega32U4 microcontroller and FUSB302 USB-C PHY. The four-layer PCB is densely packed on both sides to fit in the Arduino Pro Micro Form factor. The board can deliver up to 100W (20 V at 5 A) from an appropriate power source and shows visual feedback on the PD status through a set of LEDs.

The primary goal of the project is actually in the software. [Ryan] found that existing software libraries for PD take up a lot of memory, and are difficult to integrate into small projects. Working from the PD specifications and PD PHY chip data sheet, he created a lighter weight and self-contained software library which consumes less than 8 K of flash and 1 K of RAM. This is less than half the Flash and RAM available on the ATmega32U4.

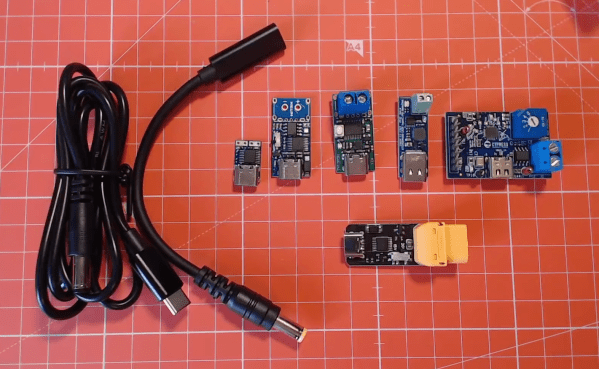

[Ryan] is running a Crowd Supply campaign (video after the break) to get some of these powerful boards out in the wild, and has released all the source code and schematics on GitHub. The PCB design files will be released during the last week of the campaign, around 25 January 2021.

USB-C and power delivery are not simple standards, but the ability to add a high-speed data interface and a programmable power supply into almost any project has real potential.

Continue reading “USB-C Programmable Power Supply For Any Project”