Historically, having a washer and a dryer in your house requires “a hookup.” You need hot and cold water for the washer as well as a drain for wastewater. For the dryer, you need either gas or — in the US — a special 220 V outlet because the heating elements require a lot of wattage, and doubling the voltage keeps the current levels manageable. You also need a bulky hose to vent hot moist air out of the house. But a relatively new technology is changing that. Instead of using a heater, these new dryers use a heat pump, and [Matt Ferrell] shows us his dryer and discusses the pros and cons in a video you can below. We liked it because it did get into a bit of detail about the principle of operation.

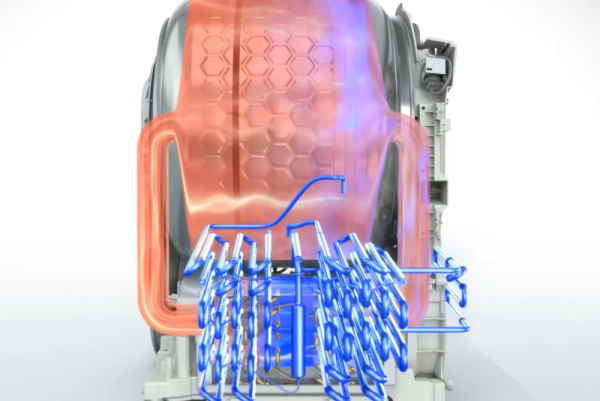

These dryers are attractive because they use less power and don’t require gas or a 220 V outlet. They also don’t need a vent hose which means they can sit much closer to the wall and take up less space. Heat pumps don’t convert electrical energy into heat like a normal heating element. Instead, it uses a compressor to move heat from one place to another. In this case, the dryer heats the air using the heat pump. That causes water in the clothes to evaporate into the air. The heat pump dryer then uses a second loop to cool the air, condensing the water out so the it can reheat the air and start the whole cycle over again.