So far we have discussed the basics of CAN, in-vehicle networks, and protocols used over CAN. We’re going to wrap up with a discussion of CAN tools, and parts to build your own CAN hardware.

Wiring

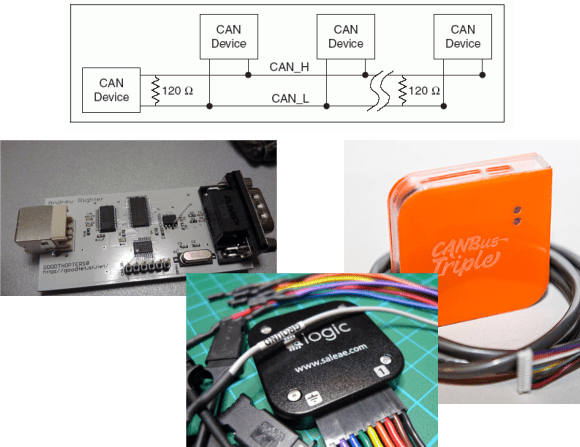

Unfortunately, there’s no set standard for CAN connections. The most common connector for high-speed CAN is a DE-9, with CAN high on pin 7 and CAN low on pin 2. However cables will differ, and many are incompatible.

CAN needs to be terminated, preferably by a 120 ohm resistance on either end of the bus. In practice, you can stick a single 120 ohm resistor across the bus to deal with termination.

Tools

A good CAN tool will let you transmit and receive CAN messages, interpret live data using CAN databases, and talk CAN protocols. The tools with this feature set are proprietary and expensive, but some hacker friendly options exist.

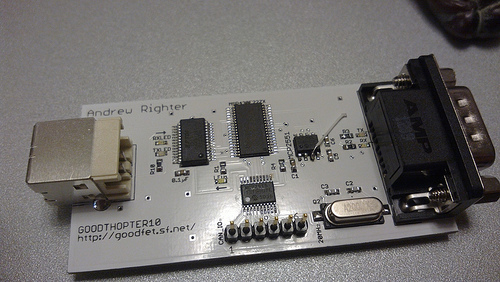

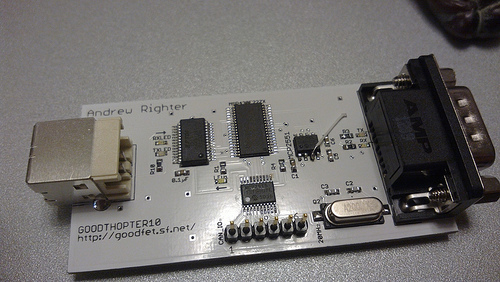

GoodThopter

Based on [Travis Goodspeed’s] GoodFET, the GoodThopter by [Q] uses the Microchip MCP2515 CAN to SPI controller to access the bus. The open hardware tool lets you send and receive messages using Python scripts.

CAN Bus Triple

The CAN Bus Triple device provides an interface to three CAN buses, and can be programmed in an environment similar to Arduino. The open source code provided lets you muck with the second generation Mazda 3. Unfortunately, the hardware does not appear to be open source.

Saleae Logic

It’s not open source, but the Saleae Logic is a very handy and cheap tool for looking at CAN buses. It can capture, decode, and display CAN traffic. This is most useful when you’re building your own CAN hardware.

DIY

The Parts

If you want to design your own hardware for CAN, you’ll need two things: a CAN controller, and a CAN transceiver.

The CAN controller generates and interprets CAN messages. There’s many microcontrollers on the market with built-in CAN controllers, such as the Atmel ATmega32M1, Freescale S08D, and the TI Tiva C Series. When using a built-in CAN controller, you’ll have to use an external oscillator, internal oscillators are not sufficiently accurate for high-speed CAN. If you want to add CAN to an existing microcontroller, the MCP2515 is an option. It’s a standalone CAN controller that communicates over SPI.

The transceiver translates signals from the controller to the bus, and from the bus to the transceiver. Different transceivers are needed for high-speed and low-speed CAN networks. The NXP TJA1050 works with high-speed buses, and the ON Semi NCV7356 works with low-speed, single wire buses.

Dev Boards

There’s a ton of development boards out there featuring microcontrollers with a CAN controller. The Arduino Due‘s SAM3 processor has a controller, but there’s no transceiver on the board. You can pick up a CAN bus shield, and the Due CAN Library to get started.

The ChipKIT Max32 is similar to the Due. It has two CAN controllers, but you’ll need to provide external transceivers to actually get on a bus. Fortunately there’s a shield for that. The ChipKIT is officially supported by Ford’s OpenXC Platform, so you can grab their firmware.

That concludes our discussion of CAN Hacking. Hopefully you’re now ready to go out and experiment with the protocol. If you have questions, send them along to our tip line with “CAN Hacking” in the subject, and we’ll compile some answers. If you liked this series and want to suggest a topic for the next set of posts we’d love to hear that as well!

CAN Hacking