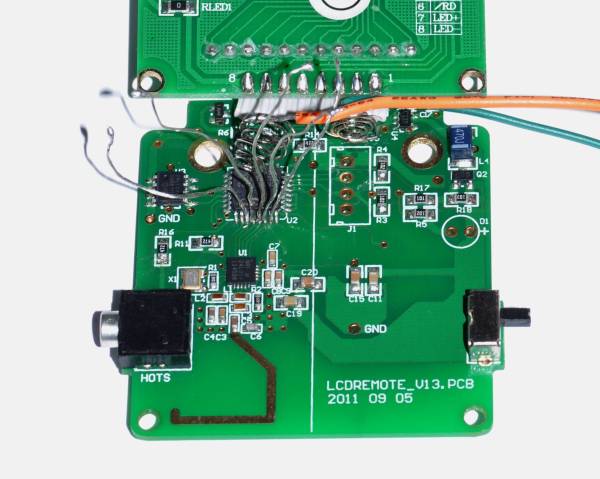

The development of the Hackaday community offline password keeper has been going on for a little less than a year now. Since July our beta testers have been hard at work giving us constant suggestions about features they’d like to see implemented and improvements the development team could make. This led up to more than 1100 GitHub commits and ten thousand lines of code. As you can guess, our little 8bit microcontroller’s flash memory was starting to get filled pretty quickly.

One of our contributors, [Miguel], recently discovered one compilation and one linker flags that made us save around 3KB of Flash storage on our 26KB firmware with little added processing overhead. Hold on to your hats, this write-up is going to get technical…

Many coders from all around the globe work at the same time on the Mooltipass firmware. Depending on the functionality they want to implement, a dedicated folder is assigned for them to work in. Logically, the code they produce is split into many C functions depending on the required task. This adds up to many function calls that the GCC compiler usually makes using the CALL assembler instruction.

This particular 8-bit instruction uses a 22-bit long value containing the absolute address of the function to call. Hence, a total of 4 flash bytes are used per function call (without argument passing). However, the AVR instruction set also contains another way to call functions by using relative addressing. This instruction is RCALL and uses an 11-bit long value containing the offset between the current program counter and the function to call. This reduces a function call to 2 bytes and takes one less clock cycle. The -mrelax flag therefore made us save 1KB by having the linker switch CALL with RCALL instructions whenever possible.

Finally, the -mcall-prologues compiler flag freed 2KB of Flash storage. It creates master prologue/epilogue routines that are called at the start and end of program routines. To put things simply, it prepares the AVR stack and registers in a same manner before any function is executed. This will therefore waste a little execution time while saving a lot of code space.

More space saving techniques can be found by clicking this link. Want to stay tuned of the Mooltipass launch date? Subscribe to our official Google Group!

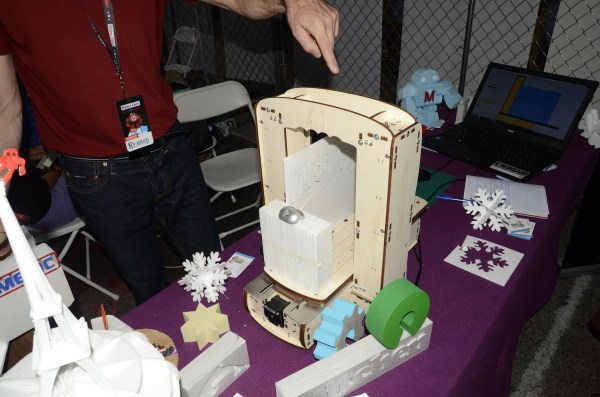

epper motors much like a 3D printer. Rather than print though, it pulls a heated nichrome wire through styrofoam. Foam cutting is great for crafts, but it really takes off when used for R/C aircraft. [Renaud] was cutting some models out of

epper motors much like a 3D printer. Rather than print though, it pulls a heated nichrome wire through styrofoam. Foam cutting is great for crafts, but it really takes off when used for R/C aircraft. [Renaud] was cutting some models out of

This project is

This project is