![]()

The HackFFM hackerspace in Frankfurt finally got their CO2 laser up and running, and the folks there were looking for something to engrave. They realized the labels on IC packages are commonly laser engraved, so they made a DIP-sized Arduino. The pins are labelled just as they would be on an Arduino, and a few SMD components dead bugged onto the pins provide all the required circuitry. Video here.

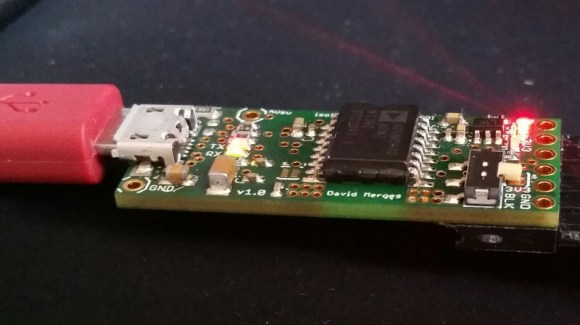

A few years ago, we heard [David Mellis] built a DIY cell phone for an MIT Media Lab thingy. Apparently it’s making the blog rounds again thanks to the Raspi cell phone we featured yesterday. Here’s the Arduino cell phone again. Honestly we’d prefer the minimalist DIY Nokia inspired version.

The Raspberry Pi is now a form factor, with the HummingBoard, a Freescale i.MX6-powered clone, being released soon. There’s another form factor compatible platform out there, the Banana Pi, and you can actually buy it now. It’s an ARM A20 dual core running at 1GHz, Gig of RAM, and Gigabit Ethernet for about $60. That SATA port is really, really cool, too.

[Richard] has been working on a solar-powered sun jar this winter and now he’s done. The design uses two small solar panels to charge up two 500F (!) supercapacitors. There’s a very cool and very small supercap charging circuit in there, and unless this thing is placed in a very dark closet, it’ll probably keep running forever. Or until something breaks.

Here’s something awesome for the synth heads out there: it’s an analog modeling synthesizer currently on Indiegogo. Three DCOs, 18dB lowpass filter, 2 envelopes and an LFO, for all that classic Moog, Oberheim, and Roland goodness. It’s also pretty cheap at $120 USD. We really don’t get enough synth and musical builds here at Hackaday, so if you’re working on something, send it in.

A glass-based PCB? Sure. Here’s [Masataka Joei] put gold and silver on a piece of glass, masked off a few decorative shapes, and sandblasted the excess electrum away. [Masataka] is using it for jewelery, but the mind races once you realize you could solder stuff to it.

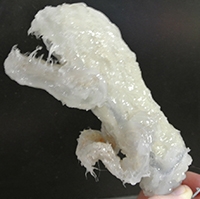

The folks at the LVL1 hackerspace had the idea of making a life-sized game of Operation. This plan changed when someone at the hackerspace had the great idea of

The folks at the LVL1 hackerspace had the idea of making a life-sized game of Operation. This plan changed when someone at the hackerspace had the great idea of