Cooking a turkey right is serious business this time of year. With major holidays on the line, there’s no room for error – any mistake can leave guests disgruntled and starving. [Stephen Farnsworth] took a risk, though, and attempted to cook a turkey using AA batteries.

The allure of the AA for such a task is precisely because it’s such a poor choice. Designed for portability rather than high power output, it was never designed to be the energy source for a major cooking job. To get things over the line, [Steve] busted out the math to figure out how many batteries would be required. This involved computing cooking efficiencies, battery thermal performance, and the specific heat of the bird itself. With the numbers coming together a 300W slow cooker was put on duty, in order to avoid over-draining the batteries.

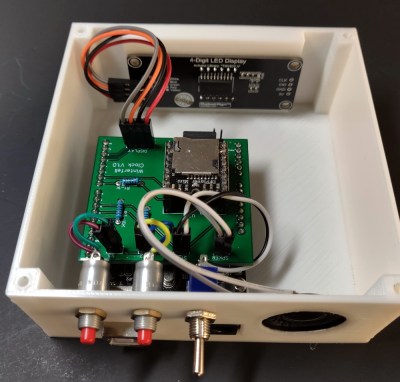

With 880 AAs loaded into a custom carrier, [Steve] hooked up the power meter and the cooker and kept a close eye on the temperatures. After a couple of hours, the battery pack started to heat up, so additional cooling was brought in to avoid fire. At just before the six hour mark, the turkey was cooked through and ready to eat. Estimates are that the batteries still had plenty of capacity to keep going for a few hours yet, too.

It’s not a fast or effective way to cook a turkey, but it’s certainly achievable. We fully expect [Steve] to submit the coin-cell turkey cook-off next year, too. Remember, a little engineering always helps, especially in the kitchen. Video after the break.