Complex behaviors can arise from simple mechanics, and that’s demonstrated by a block of rubber that acts as a counter.

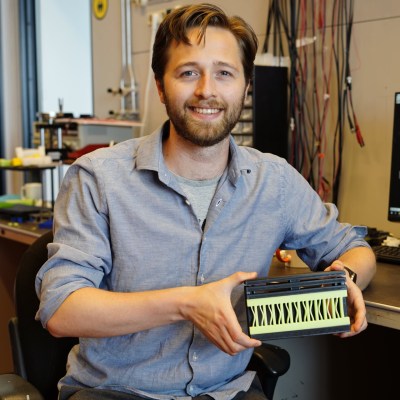

The block contains beams, and by controlling how the block is compressed, the vertical beams shift in a stable and consistent way, acting as a mechanical counter. It’s a straightforward implementation of the work of two physicists from the Netherlands: [Martin van Hecke] and [Lennard Kwakernaak].

The block contains beams, and by controlling how the block is compressed, the vertical beams shift in a stable and consistent way, acting as a mechanical counter. It’s a straightforward implementation of the work of two physicists from the Netherlands: [Martin van Hecke] and [Lennard Kwakernaak].

This device brings flexures to mind, which are also examples of obtaining complex and useful behavior from seemingly simple objects. We’ve seen flexures used as latches and counters, and we’ve seen 3D printed flexures as a kind of linear actuator.

You can check out the research paper for more details on the rubber beam counter. [Kwakernaak] aims to create a much more complex structure with elements that interact across a plane instead of in a single direction. Such a device would, in effect, be a simple computer.

Watch the beam counter in action in the short video embedded below. See how the elements of the green rubber block move while constrained by an outer frame that helps control the force that is applied. The thin beams flip from left to right, one at a time with each press.