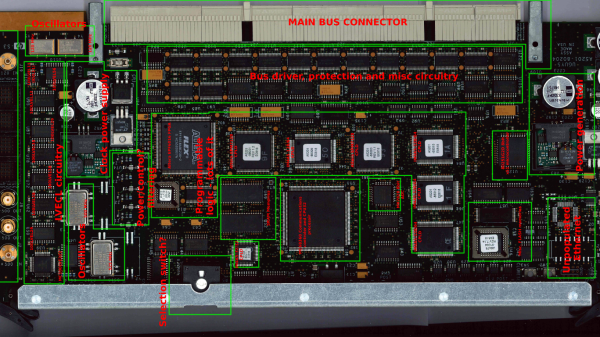

As interesting as it is to look at the insides of de-capped chips, it is equally interesting to sometimes look at old circuit boards and try to figure out the various sections, their functions, and to look at some of the design practices used. At a local electronics flea market, [daqq] recently chanced upon quite a large PCB that seemed to have come from some HP system, and picked it up for about €6 – the value of the abundant oscillators, crystals, connectors and other miscellaneous components that could be recovered seemed much more than what he paid for the board.

The board in question turned out to be from a HP 9000 Superdome system – part of the PA-8xxx based server series which packs quite a punch. This particular one was the 500MHz system UGUY5-500 board. At this point, most of [daqq]’s analysis is based on what he can visually decipher looking at the chip numbers and associated parts. He’s taken a stab at guessing the function of the board itself, and of the various parts on it. He’s put up high resolution scanned images of the board, for any of our readers who would like to offer an insight in to this board or the system that it was part of. Apparently, he has quite a few more exotic server PCB’s lined up for sleuthing, if you folks enjoy this.