Recently, you might have noticed a flurry of CH552 projects on Hackaday.io – all of them with professionally taken photos of neatly assembled PCBs, typically with a USB connector or two. You might also have noticed that they’re all built by one person, [Stefan “wagiminator” Wagner], who is a prolific hacker – his Hackaday.io page lists over a hundred projects, most of them proudly marked “Completed”. Today, with all these CH552 mentions in the Hackaday.io’s “Newest” category, we’ve decided to take a peek.

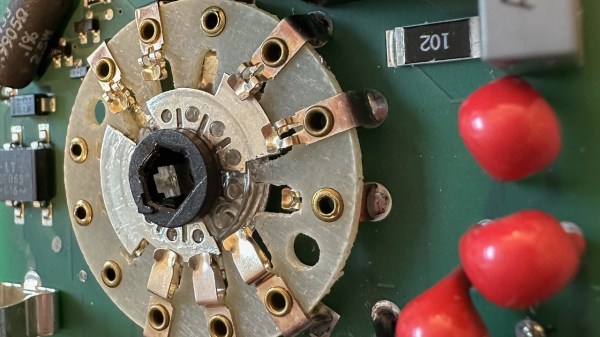

The CH552 is an 8-bit MCU with a USB peripheral, with a CH554 sibling that supports USB host, and [Stefan] seriously puts this microcontroller to the test. There’s a nRF24L01+ transceiver turned USB dongle, a rotary encoder peripheral with a 3D-printed case and knob, a mouse wiggler, an interface for our beloved I2C OLED displays, a general-purpose CH55x devboard, and a flurry of AVR programmers – regular AVRISP, an ISP+UPDI programmer, and a UPDI programmer with HV support. Plus, if USB host is your interest, there’s a CH554 USB host development board specifically. Every single one of these is open-source, with PCBs designed in EasyEDA, the firmware already written (!) and available on GitHub, and a lovingly crafted documentation page for each.

[Stefan]’s seriously put the CH552 to the test, and given that all of these projects got firmware, having these projects as examples is a serious incentive for more hackers to try these chips out, especially considering that the CH552 and CH554 go for about 50 cents a piece at websites like LCSC, and mostly in friendly packages. We did cover these two chips back in 2018, together with a programming guide, and we’ve seen things like badges built with its help, but having all these devices to follow is a step up in availability – plus, it’s undeniable that all the widgets built are quite useful by themselves!

![A Hackaday.io page screenshot, showing all the numerous CH552 projects from [Stefan].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/hadimg_ch552_projects_feat.png?w=600&h=450)