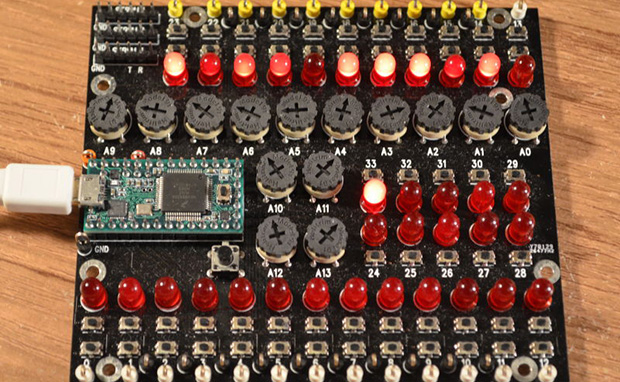

Sometimes with a microcontroller project you need to do some very RAM-hungry operations, like image and audio processing. The largish AVR chips are certainly fast enough to do these tasks, but the RAM on these chips is limited. [xxxajk] has come up with a library that allows the use of huge RAM expansions with the Teensy++ 2.0 microcontroller, making these RAM-dependant tasks easy on one of our favorite microcontroller board.

[xxajk]’s work is actually a port of XMEM2, an earlier project of his that added RAM expansion and multitasking to the Arduino Mega. Up to 255 banks of memory are available and with the supported hardware, the Teensy can address up to 512kB of RAM.

XMEM2 also features a preemptive multitasking with up to 16 tasks, the ability to pipe messages between tasks, and all the fun of malloc().

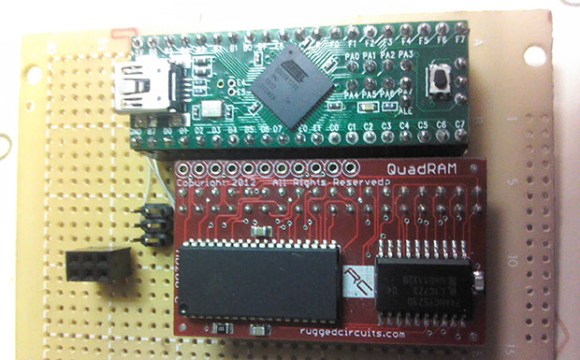

The build is fairly hardware independent, able to work with Rugged Circuits QuadRAM and MegaRAM expansions for the Arduino Mega as well as [Andy Brown]’s 512 SRAM expansion. With the right SRAM chip, etching a board at home for XMEM2 is also a possibility.