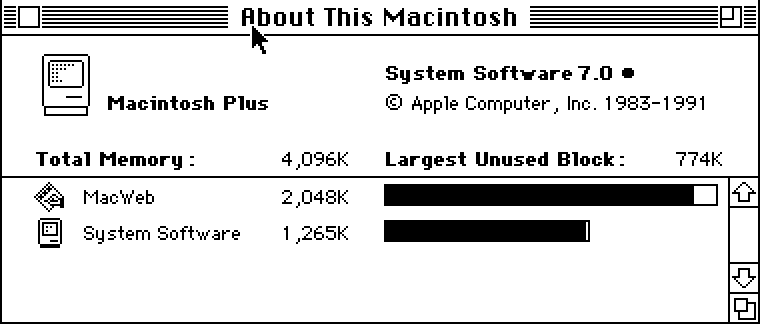

[Jeff] has a Mac Plus, an 8 MHz computer with 4 MB of RAM and a 512×342 1-bit screen. It was his first ‘real’ computer, and like those guys that take Model A Fords out for a Sunday drive, [Jeff] decided to put this old box on the Internet.

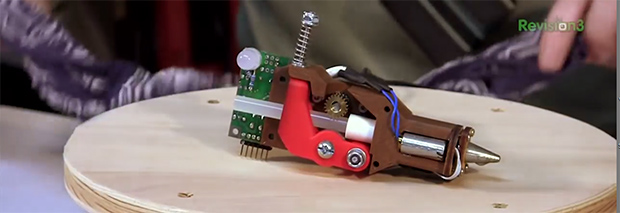

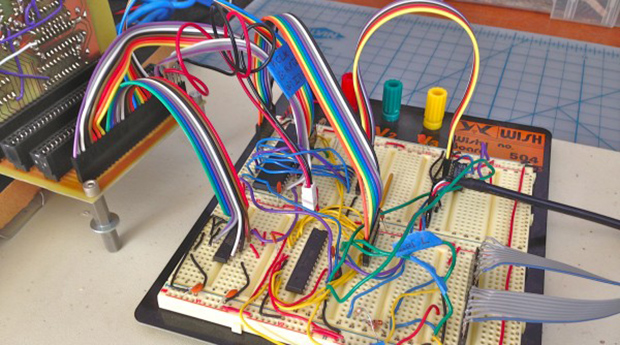

A Plus has a few options to get on the Internet. The best, but most expensive, is a SCSI to Ethernet computer. For a somewhat slower connections, a PowerPC mac can be used as an Ethernet to Localtalk (the Macintosh serial port networking protocol) bridge. Lacking either of those pieces of hardware, [Jeff] decided to use a Raspberry Pi. The Pi does the heavy lifting, and a handful of serial adapters and voltage converters turns the Pi into something that can talk to the Plus’ serial port.

Even with the MacTCP stack and the MacWeb browser, there are still some things this ancient computer couldn’t do. HTTPS hadn’t been invented until 1994, cookies are just a pain, and CSS is right out. This means modern websites (except, of course, the Hackaday retro edition) simply won’t render properly. To fix this issue, [Jeff]’s friend [Tyler] came up with a Python script using Requests, Beautiful Soup, and Flask to strip out all the Web 2.0 cruft, handle the cookies, and to get rid of SSL.

The end result is a Mac Plus with 4 Megabytes of RAM on the Internet, able to pull up Wikipedia and Hacker News. It isn’t fast by any means – in the video below, it takes about five minutes to pull up the front page of Hacker News – but it is a 27-year-old computer on the Internet.