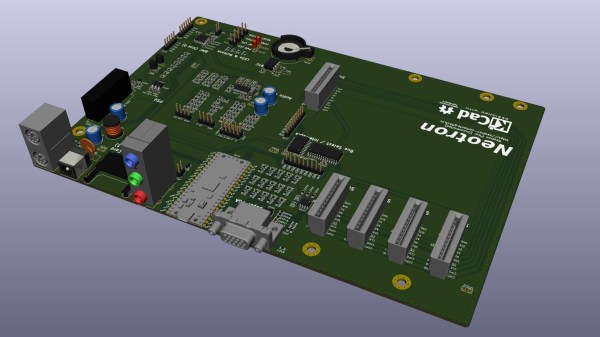

[Andrew Lamchenko], who has built a number of small e-ink-based sensors this year, released another design called the eON Indoor Air Quality Sensor. As his previous sensor designs, the eON boasts a striking appearance with all the spit and polish of a commercially made product. Except [Andrew]’s design is completely open-source.

Besides showing air quality, it also shows basic weather conditions, and there’s a built-in weather forecasting algorithm as well. It can operate standalone or use the radio module to send readings to a smart home system.

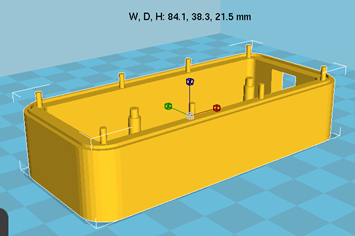

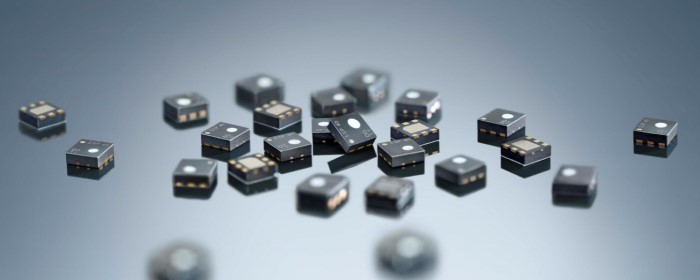

The core sensor is the SGP40, which detects volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the air while consuming less than 3 mA (compared to the 48 mA of the previous generation). There’s a temperature, barometric pressure, humidity, and light sensors in the package as well. Like many projects these days, [Andrew] encountered parts supply issues along the way. Because of that, and to make the design more flexible, several versions of the board have been made to accommodate the different permutations of:

- Displays

- 2.13-inch e-ink display

- DES e-ink display, coming soon

- Radio, four flavors

- MINEW MS88SF3 (nRF52833, nRF52840)

- MINEW MS50SFA1 (nRF52810, nRF52811)

- MINEW MS50SFA2 (nRF52832)

- EBYTE E73-2G4M08S1C (nRF52833, nRF52840)

- Temp / Pressure sensor:

- BME280

- BMP280

- SHTC3

[Andrew] not only designed the sensor but has done a thorough job on the documentation. Check out the GitHub repository of the project for a complete data package covering all aspects of the design, including the weather forecasting app note by John Young (an NXP engineer, not the astronaut). Last week the design was named as a finalist of the 2021 Hackaday Prize. We’re excited to see where he goes with this between now and the end of October!

Do you use an air quality sensor in your home? If so, is it only for informational purposes or do you take action based on the data, such as automatically turning on a fan or escaping to the countryside? Let us know in the comments below.