Fair warning: watching this hybrid manufacturing method for gear teeth may result in an uncontrollable urge to buy a fiber laser cutter. Hackaday isn’t responsible for any financial difficulties that may result.

With that out of the way, this is an interesting look into how traditional machining and desktop manufacturing methods can combine to make parts easier than either method alone. The part that [Paul] is trying to make is called a Hirth coupling, a term that you might not be familiar with (we weren’t) but you’ve likely seen and used. They’re essentially flat surfaces with gear teeth cut into them allowing the two halves of the coupling to nest together and lock firmly in a variety of relative radial positions. They’re commonly used on camera gear like tripods for adjustable control handles and tilt heads, in which case they’re called rosettes.

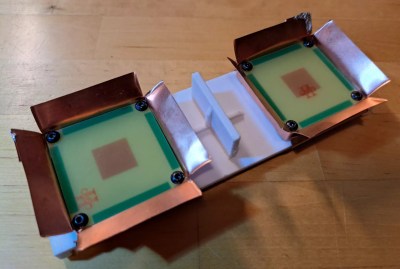

To make his rosettes, [Paul] started with a block of aluminum on the lathe, where the basic cylindrical shape of the coupling was created. At this point, forming the teeth in the face of each coupling half with traditional machining methods would have been tricky, either using a dividing head on a milling machine or letting a CNC mill have at it. Instead, he fixtured each half of the coupling to the bed of his 100 W fiber laser cutter to cut the teeth. The resulting teeth would probably not be suitable for power transmission; the surface finish was a bit rough, and the tooth gullet was a little too rounded. But for a rosette, this was perfectly acceptable, and probably a lot faster to produce than the alternative.

In case you’re curious as to what [Paul] needs these joints for, it’s a tablet stand for his exercise machine. Sound familiar? That’s because we recently covered his attempts to beef up 3D prints with a metal endoskeleton for the same project.

Continue reading “Lathe And Laser Team Up To Make Cutting Gear Teeth Easier”