You whippersnappers these days with your 3D printers! Back in our day, we had to labor over a blank for hours, getting all sweaty and covered in foam dust. And it still wouldn’t come out symmetric. Shaping a surfboard used to be an art, and now you’re just downloading software and slinging STLs.

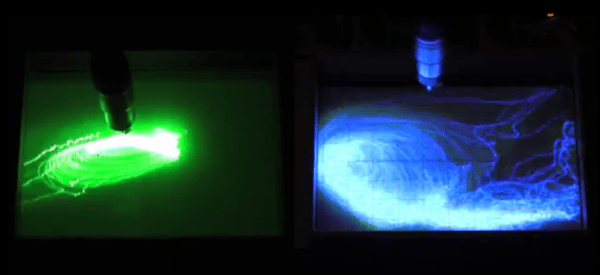

Joking aside, [Jody] made an incredible surfboard (yes, actual human-sized surfboard) out of just over 1 kilometer of ABS filament, clocking 164 hours of printing time along the way. That’s a serious stress test, and of course, his 3D printer broke down along the way. Then all the segments had to be glued together.

But the printing was the easy part; there’s also fiberglassing and sanding. And even though he made multiple mock-ups, nothing ever goes the same on opening night as it did in the dress rehearsal. But [Jody] persevered and wrote up his trials and tribulations, and you should give it a look if you’re thinking of doing anything large or in combination with fiberglass.

Even the fins are 3D printed and the results look amazing! We can’t wait for the ride report.

Shaka.