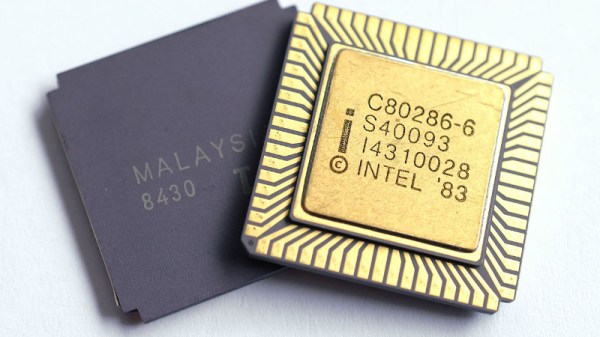

The Internet, or at least our corner of it, has been abuzz over the last few days with the news of a DEF CON talk by [Sick.Codes] in which he demonstrated the jailbreaking of the console computer from a John Deere tractor. Sadly we are left to wait the lengthy time until the talk is made public, and for now the most substantive information we have comes from a couple of Tweets. The first comes from [Sick.Codes] himself and shows a game of DOOM with a suitably agricultural theme, while the second is by [Kyle Wiens] and reveals the tractor underpinnings relying on outdated and un-patched operating systems.

You might ask why this is important and more than just another “Will it run DOOM” moment. The answer will probably be clear to long-term readers, and is that Deere have become the poster child for improper use of DRM to lock owners into their servicing and deny farmers the right to repair. Thus any breaches in their armor are of great interest, because they have the potential to free farmers world-wide from this unjust situation. As we’ve reported before the efforts to circumvent this have relied on cracked versions of the programming software, so this potential jailbreak of the tractor itself could represent a new avenue.

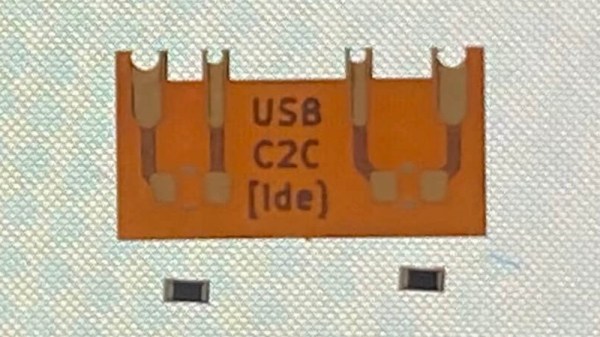

As far as we’re aware, this has so far taken place on the console modules in the lab and not in the field on a real tractor. So we’re unsure as to whether the door has been opened into the tractor’s brain, or merely into its interface. But the knowledge of which outdated software can be found on the devices will we hope lead further to what known vulnerabilities may be present, and in turn to greater insights into the machinery.

Were you in the audience at DEF CON for this talk? We’d be curious to know more. Meanwhile the Tweet is embedded below the break, for a little bit of agricultural DOOM action.

Continue reading “Did You See A John Deere Tractor Cracked At DEF CON?”