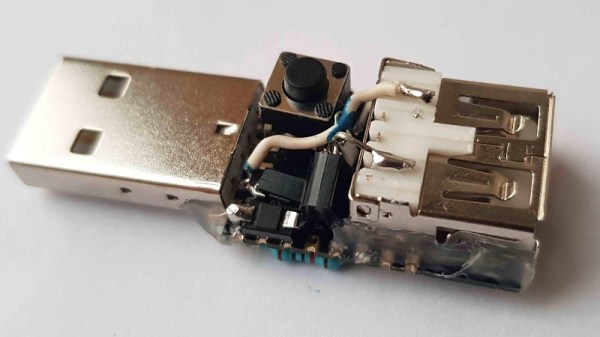

UPnP — in a perfect world it would have been the answer to many connectivity headaches as we add more devices to our home networks. But in practice it the cause of a lot of headaches when it comes to keeping those networks secure.

It’s likely that many Hackaday readers provide some form of technical support to relatives or friends. We’ll help sort out Mom’s desktop and email gripes, and we’ll set up her new router and lock it down as best we can to minimise the chance of the bad guys causing her problems. Probably one of the first things we’ll have all done is something that’s old news in our community; to ensure that a notorious vulnerability exposed to the outside world is plugged, we disable UPnP on whatever cable modem or ADSL router her provider supplied.

Continue reading “UPnP, Vulnerability As A Feature That Just Won’t Die”