Many Hackaday readers may also be familiar with the Discworld series of fantasy novels from [Terry Pratchett], and thus might recognise a weapon referred to as the Piecemaker. A siege crossbow modified to launch a hail of supersonic arrows, it was the favoured sidearm of a troll police officer, and would frequently appear disintegrating large parts of the miscreants’ Evil Lairs to comedic effect.

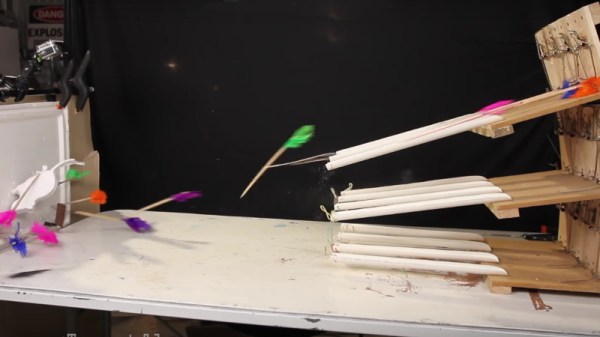

Just as a non-police-officer walking the streets of Ank-Morpork with a Piecemaker might find swiftly themselves in the Patrician’s scorpion pit, we’re guessing ownership of such a fearsome weapon might earn you a free ride in a police car here on Roundworld. But those of you wishing for just a taste of the arrow-hail action needn’t give up hope, because [Turnah81] has made something close to it on a smaller scale. His array of twelve mousetrap-triggered catapults fires a volley of darts made from wooden kebab skewers in an entertaining fashion, and has enough force to penetrate a sheet of cardboard.

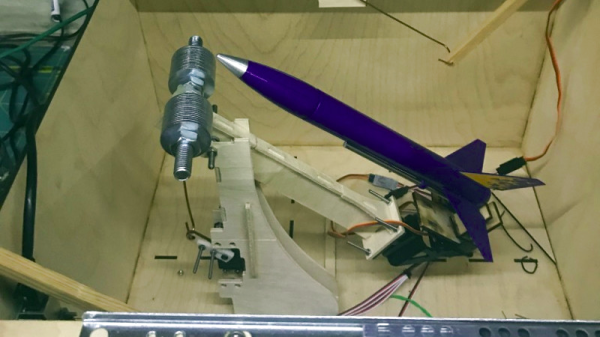

He refers to a previous project with a single dart, and this one is in many respects twelve of that project in an array. But in building it he solves some surprisingly tricky engineering problems, such as matching the power of multiple rubber bands, or creating a linkage capable of triggering twelve mousetraps (almost) in unison. His solution, a system of bent coat-hanger wires actuated by the falling bar of each trap, triggers each successive trap in a near-simultaneous crescendo of arrow firepower.

On one hand this is a project with more than a touch of frivolity about it. But the seriousness with which he approaches it and sorts out its teething troubles makes it an interesting watch, and his testing it as a labour-saving device for common household tasks made us laugh. Take a look, we’ve put the video below the break.

Continue reading “Rapid-Fire Hail Of Chopstick Arrows Makes Short Work Of Diminutive Foes”