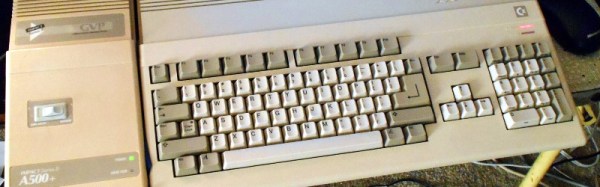

If you were lucky enough to have a Commodore Amiga or one of its competitor 16-bit home computers around the end of the 1980s, it’s probable that you were doing all the computing tasks that most other people discovered a few years later when they bought their first 486 or Pentium. So in the mid 1990s when all your friends were exclaiming at Paint Shop Pro or their Soundblaster cards you’d have had an air of smugness. Multitasking? Old hat! Digital audio? Been there! Graphics manipulation? Done that!

There was one task from that era you almost certainly wouldn’t have done on your Amiga though, and that was connect it to the Internet. The Internet was certainly a thing back in the late 1980s, but for mere mortals it was one of those unattainable marvels, like a supercomputer with a padded seat round it, or a Jaguar XJ220 supercar.

Later Amigas received Internet abilities, and Amiga enthusiasts will no doubt be on hand to extol their virtues. But the machine most people will think of as the archetype, the Amiga 500, lacks the power to run most of the software required to do it. If your 500 with its tasteful blue and orange desktop colour scheme is languishing though, never fear. [Shot97] has produced a guide to getting it online.

It’s important to understand that an Amiga 500 is never going to run a copy of Chrome or play a YouTube video. And he makes the point that any web browsers that might have surfaced for hardware of this class delivered a painful browsing experience. So instead he concentrates on getting the 500 online for something closer to the online scene of the day, connecting to BBSs. To that end he takes us through setting up a PC with Hayes modem emulator, and connecting it to the Amiga via a null modem cable. On the Amiga is a copy of the A-Talk terminal emulator, and as far as the Amiga is concerned it is on a dial-up Internet connection.

The PC in this case looks pretty ancient, and we can’t help wondering whether a Raspberry Pi or even an ESP8266 module could be put in its place given the appropriate software. But he has undeniably got his A500 online, and shown a way that you can too if you still have one lurking in the cupboard. He has also produced a video which we’ve put below the break, but be warned, as it’s nearly an hour long.

Continue reading “Getting The Amiga 500 Online” →