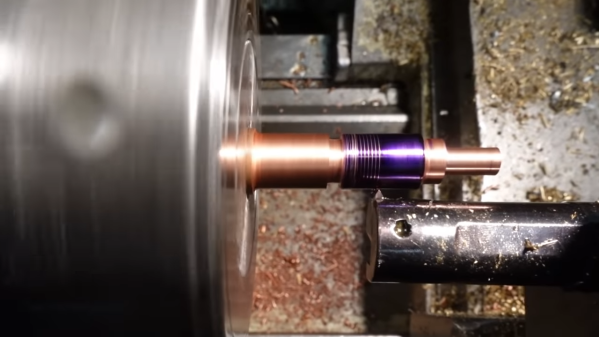

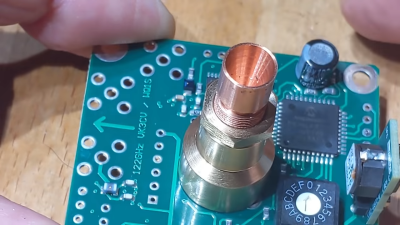

Millimeter-wave Radars used in modern cars for cruise control and collision avoidance are usually designed to work at ranges on the order of 100 meters or so. With some engineering nous, however, experimenters have gotten these devices sending signals over ranges of up to 60 km in some tests. [Machining and Microwaves] decided to see if he could push the boat out even further, and set out machining some waveguide combiner cavities so he could use the radar chips with some very high-performance antennas.

The end goal of the project is to produce a 53 dBi antenna for the 122GHz signal put out by the mmWave radar chips commonly found in automotive applications. Working at this frequency requires getting tolerances just so in order to create an antenna that performs well.

Plenty of fine lathe work and cheerful machining banter later, and the precision waveguide is done. It may not look like much to the untrained eye, but much careful design and machining went on to make it both easy to attach to the radar and parabolic antenna system, and to make it perform at a high enough level to hopefully break records set by other enterprising radio experimenters. If that wasn’t all hard enough, though, the final job involved making 24 of these things!

There aren’t a whole lot of microwave antenna-specific machining channels on YouTube, so if you’ve been thirsty for that kind of content, this video is very much for you. If you’re more interested in antennas for lower frequencies, though, you might find some of our other stories to your liking. Video after the break.

Continue reading “Machining Waveguides For 122 GHz Operation Is Delicate Work”