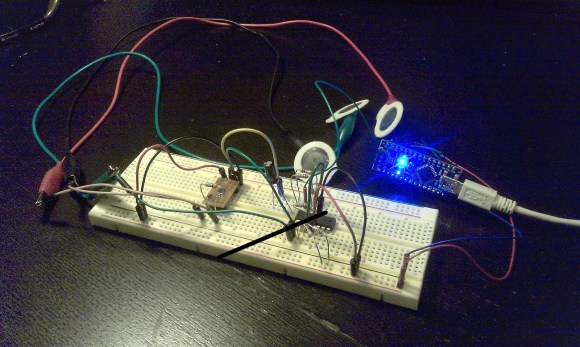

Check out all the stuff crammed into a small swath of strip board. It’s got that characteristic look of a roll-your-own Arduino board, which is exactly what it is. [S. Erisman] shows you how to build your own copy of his YABBS; Yet Another Bare Bones Arduino (on Stripboard).

The strips of copper on the bottom of the substrate run perpendicular to the DIP chip and have been sliced in the middle. This greatly reduces the amount of jumpering that would have been necessary if using protoboard. A few wires make the necessary connections between the two tooled SIL headers that make up the chip socket. On the right hand side there a voltage regulator with smoothing caps. The left side hosts the obligatory pin 13 LED, and the crystal oscillator can be glimpsed on the far side of the ATmega328.

Pin headers along either side of the board have been altered to allow for soldering from the wrong side of the plastic frames. Note that there’s a three-pin hunk that breaks out the voltage regulator, and an ISP programming header sticking out the top to which those female jumper wires are connected.

Ringing in at as little as $2-$4.75 a piece you’ll have no problem leaving this in a project for the long hall. We can’t say the same for a $30+ brand name unit.