In the art world, it’s often wistfully said that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. In the open-source hardware world, this flattery takes the shape of finding your open-source project mass produced in China and sold at outrageously low markups. Looking around on my lab, I’ve been the direct beneficiary of this success.

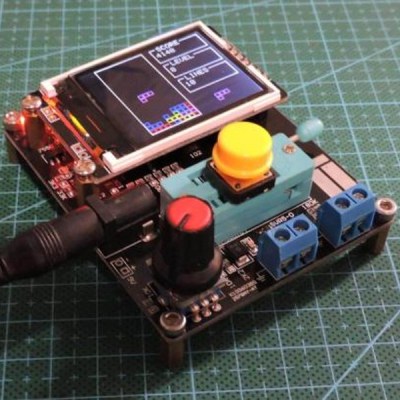

I see an AVR Transistor Tester that I picked up for a few bucks a long time ago. Lacking anything better, it’s my go-to device for measuring inductance and capacitor ESR. For $7, it is worth much more than I paid for it, due to some clever design work by a community of German hackers and the economics of mass production. They’re so cheap that we’ve seen people re-use them just for the displays and with a little modification, turned them into Tetris consoles. That’s too cool. Continue reading “The Sincerest Form Of Flattery”

I see an AVR Transistor Tester that I picked up for a few bucks a long time ago. Lacking anything better, it’s my go-to device for measuring inductance and capacitor ESR. For $7, it is worth much more than I paid for it, due to some clever design work by a community of German hackers and the economics of mass production. They’re so cheap that we’ve seen people re-use them just for the displays and with a little modification, turned them into Tetris consoles. That’s too cool. Continue reading “The Sincerest Form Of Flattery”