When we picture the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant disaster and its aftermath, we tend to recall just the commonly shared video recorded by television crews, but the unsung heroes were definitely the robotic cameras that served to keep an eye on not only the stricken reactor itself but also the sites holding contaminated equipment and debris. These camera systems are the subject of a recent video by the [Chernobyl Family] channel on YouTube, as they tear down, as well as plug in these pinnacles of 1980s vidicon-based Soviet engineering.

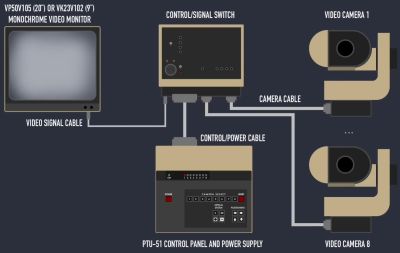

When the accident occurred at the #4 reactor at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant (ChNPP) in 1986, engineers not only scrambled to find ways to deal with the immediate aftermath but also to monitor and enter radioactive areas without exposing squishy human tissues. This is where the KTP-63 and KTP-64 cameras come into play. One is reminiscent of your typical security camera, while the other is a special model that uses a mirror instead of directly exposing the lens and tube to radiation. As a result, the latter type was quite hardy. Using a central control panel, multiple cameras could be controlled.

When mounted to remotely controlled robots, these cameras were connected to an umbilical cord that gave operators eyes on the site without risking any lives, making these cameras both literally life-savers and providing a solid template for remote-controlled vehicles in future disaster zones.

Editor’s note: Historically, the site was called Чернобыль, which is romanized to Chernobyl, but as a part of Ukraine, it is now Чорнобиль or Chornobyl. Because the disaster and the power plant occurred in 1986, we’ve used the original name Chernobyl here, as does the YouTube channel.

Continue reading “The CCTV Cameras That Recorded The Chernobyl Disaster And Aftermath”