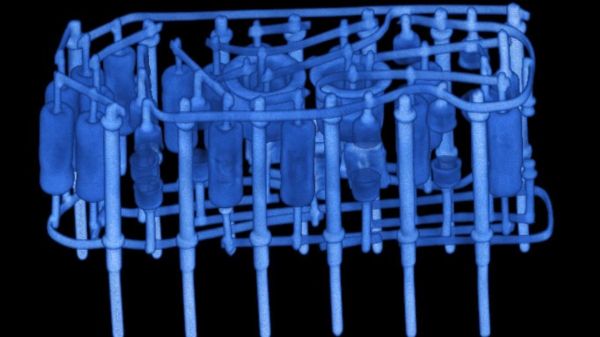

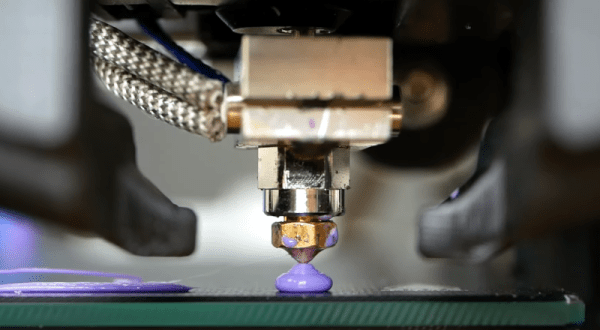

The Framework laptop project is known for quite a few hacker-friendly aspects. For example, they encourage you to reuse its motherboard as a single-board computer – making it into a viable option for your own x86-powered projects. They have published a set of CAD files for that, and people have been working on their own Framework motherboard-based creations ever since; our hacker, [whatthefilament], has already built a few projects around these motherboards. Today, he’s showing us the high-effort design that is the FrameTablet – a 15″ device packing an i5 processor, all in a fully 3D printed chassis. The cool part is – thanks to his instructions, you can build one yourself!

This tablet sports a FullHD touchscreen IPS display and shows some well-thought-out component mounting, using heat-set inserts and screws, increasing such a build’s mechanical longevity. You lose one of the expansion card slots to the USB-C-connected display, but it’s a worthwhile tradeoff, and the touchscreen functionality works wonders in Windows. [whatthefilament] has also published a desk holder and a wall mount to accompany this design – if it’s a bit too large for you to hold in some situations, you can mount it in a more friendly, hands-free way. This is a solid and surprisingly practical tablet, and unlike the Raspberry Pi tablet builds we’ve seen, its x86 heart packs enough power to let you do things like CAD on the go.

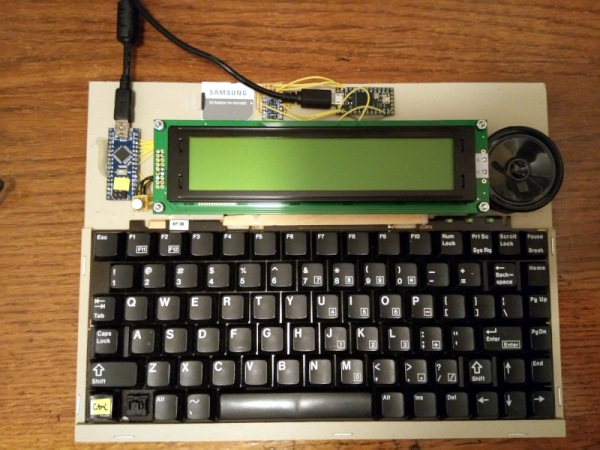

With STLs and STEPs available, his build is a decent option for when you’ll want to replace your Framework’s motherboard with a new, upgraded one. You might’ve already noticed a few high-effort projects with these motherboards on our pages – perhaps, this transparent shell handheld with a mech keyboard and trackball, or this personal terminal with a futuristic-looking round display. This project is part of the “send 100 motherboards to hackers” initiative that Framework organized a few months ago, and we can’t say it hasn’t been working out for them!

Two big drops today! I've released V1.3 of the @FrameworkPuter tablet on my GitHub, which now includes support for the stock battery, speakers, and a @iFixit style instruction manual to walk you through the build. https://t.co/cpfFSOA7fHhttps://t.co/32CVIwOB9y pic.twitter.com/WW5RsodFIC

— What the Filament (@whatthefilament) August 5, 2022