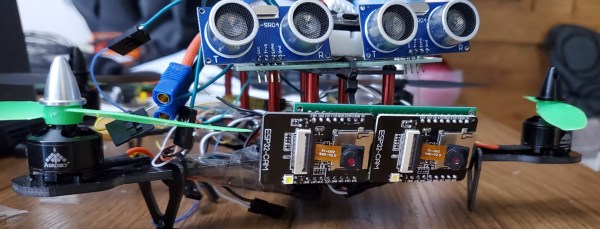

Lost aircraft are harder to find when they are physically small to begin with. Not only are they harder to see, but the smaller units lack features like GPS tracking; it’s not normally possible to add it to a tiny aircraft that can’t handle much more than its own weight in the first place. As a result, little lost quads tend to be trickier to recover in general.

The good news is that [Eric Brasseur] has shared some concise tips on how to more easily locate and recover lost aircraft, especially lightweight ones. Recovering aircraft is something every aircraft hobbyist has had to deal with in one way or another, but [Eric] really has gathered an impressive list of tricks and techniques, and some of them go into some really useful additional detail. It occurs to us that a lot of these tips could apply equally well to outdoor robots, or rovers.

Even simple techniques can be refined. For example, using bright colors on an aircraft is an obvious way to increase visibility, but some colors are better choices than others. Bright orange, white, and red are good choices because they are easily detected by the human eye while still being uncommon in nature. Violet, blue, and even cyan on the other hand may seem to be good choices when viewed indoors on a workbench, but if the quad is stuck in dark bushes, those colors will no longer stand out. Another good tip is to consider also adding a few patches of fluorescent tape to the aircraft. If all else fails, return at night with a UV lamp; those patches will glow brightly, and be easily seen from tens of meters.

Some of the tips are used while the device still has power, while others don’t depend on batteries holding out. [Eric] does a great job of summing up those and many more, so take a look. They might come in handy when test flying quadcopters that are little more than an 18650 cell, motors, and a 3D-printable frame.