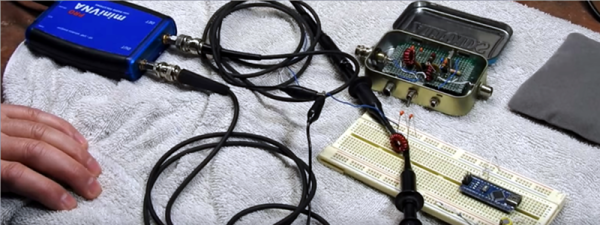

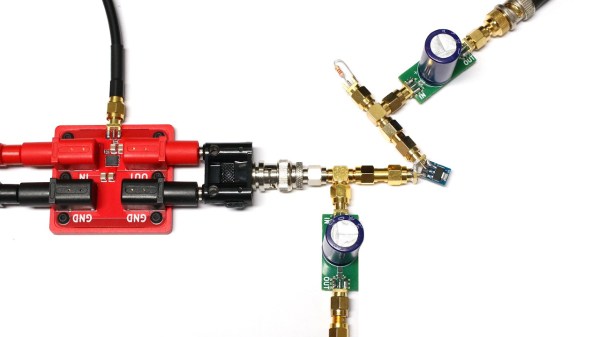

[KB9RLW] wanted to build a vector network analyzer (VNA), but then realized he could buy a ready-made one without nearly the cost it would have been only a few years ago. The network in this case, by the way, is an electrical network, not a computer network. You can use a VNA to characterize components, circuits, antennas, and even feed lines at different frequencies. The miniVNA Pro is economical and can exercise circuits from 1 MHz to 3 GHz. You can see the review in the video below.

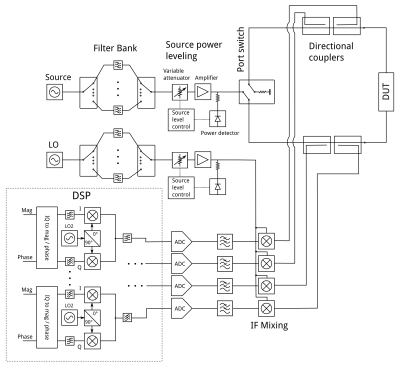

There are a few ways to actually create a VNA, but in concept, it is a sweep generator, a detector, and a means to plot the response at each frequency in the sweep. So you’d expect, for example, a resonant frequency to show a peak at resonance and a band reject filter to show a low point.

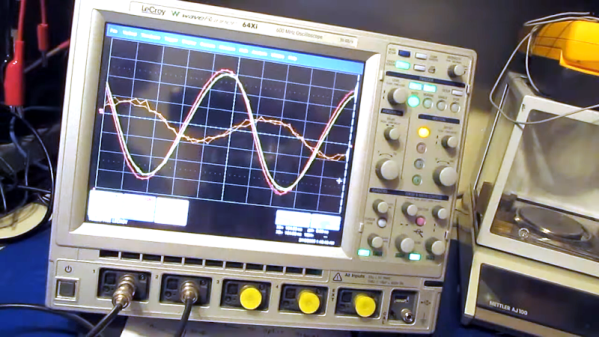

One of the things interesting about the device is that it uses Java software. That means it doesn’t care much what platform you want to use. The software can show two different plots at once, so [Kevin] hooks it to his 20 meter antenna and shows how it can plot the SWR and impedance around the frequency of interest.

The instrument can be USB powered with the same cable you use to connect the PC. However, it also has an internal rechargeable battery. That battery charges on USB and can operate the device with Bluetooth. We can imagine that being handy when you want to climb up a tower and connect it directly to an antenna as long as you stay in Bluetooth range of the PC. There’s also a phone app, so you can go that route, if you prefer and [Kevin] shows the device working with Android. Of course, you could probably rig a Raspberry Pi on your belt and then use WiFi to let someone on the ground remote desktop in to run measurements. A lot of possibilities.

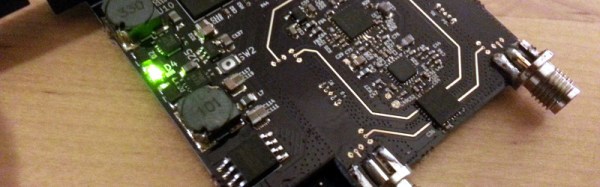

If you want to roll your own, that’s possible, of course. If you want to get by a bit cheaper, there are less expensive options.