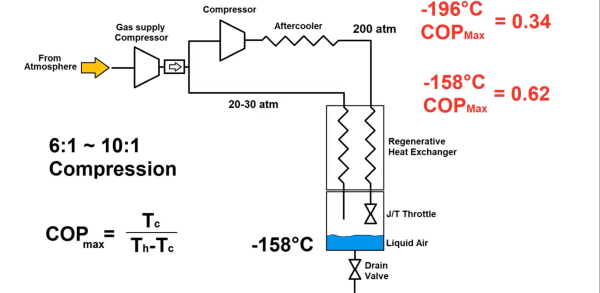

The fun part about crycoolers is that there are so many different and exciting ways to make stuff cold, based on a wide variety of physics. This is why after first exploring the Stirling/GM cycle and vapor-compression to create a cryocooler that he could liquefy nitrogen with, [Hyperspace Pirate] is exploring a Joule-Thomson cooler, which is also misspelled as ‘Joule-Thompson’ by those who don’t mind take some liberties with history. Either way, the advantage of the adiabatic Joule-Thomson effect is that it is significantly simpler than the other methods — having been invented in the 19th century and used for the earliest forms of refrigeration.

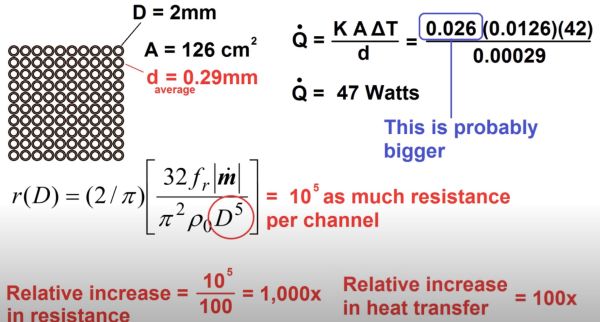

The big difference between it and other technologies is that the effect is based on throttling the flow of a gas as it seeks to expand, within specific temperature and pressure ranges to ensure that the temperature change effect is positive (i.e. the temperature of the gas decreases). The net result is that of a cooling effect, which as demonstrated in the video can be used with successive stages involving different gases, or a gas mixture, to reach a low enough temperature at which nitrogen (contained in the same gas mixture) liquefies and can be collected.

Although not a very efficient process, if your local electricity costs allow it, running the compressor in a closed loop version isn’t that expensive and worth it for the science alone. Naturally, as with any experimental setup involving a range of gases, a compressor and other components, getting it to run perfectly on the first try is basically impossible, which is why this is so far Part 1 of another series on cryocoolers at home (or in the garage).

If you’re interested in the previous work [Hyperspace Pirate] has done with DIY cyrocoolers, take a look at our coverage from earlier this year.

Continue reading “Creating A Joule-Thomson Cryocooler And A Little Bit Of History At Home”