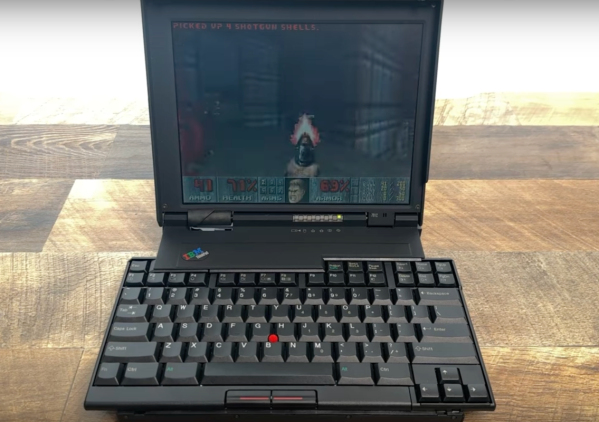

The ThinkPad 701 is an iconic laptop series from the mid-90s and is still highly sought after today because of its famous butterfly keybaord. The laptop itself is tiny even by the standards of the time, so in order to fit a full-size keyboard IBM devised a mechanism where the keyboard splits and slides over itself to hide away as the screen is closed. But, like most 30-year-old laptops, the original batteries for these computers are well past their prime. [polymatt] takes us through all of the steps needed in order to recreate a battery from this era down to the last detail.

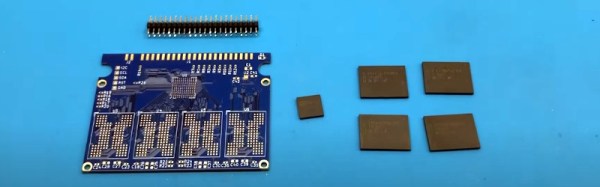

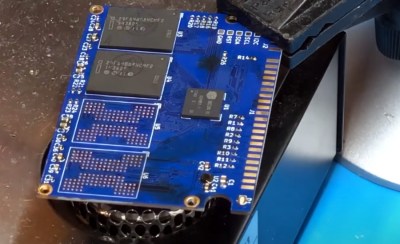

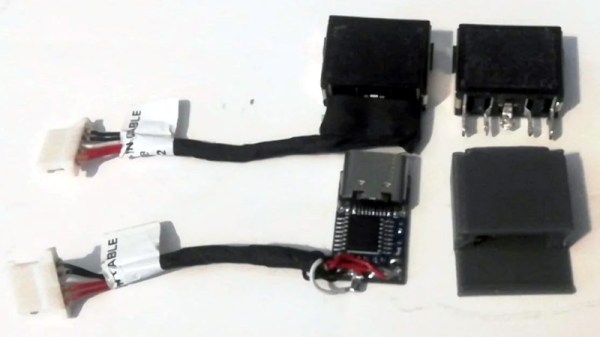

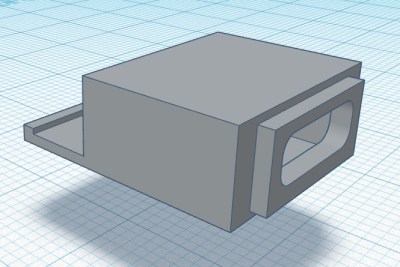

He starts by disassembling an old battery with extensive damage from the old, leaky batteries. The first part of the recreation is to measure the battery casing so a new one can be modeled and printed. The control boards for the batteries of these computers were not too sophisticated, so [polymatt] is able to use a logic analyzer with a working unit to duplicate its behavior on an ATtiny microcontroller. With that out of the way, a new PCB is created to host the cloned chip and a new battery pack, made out of 9 NiMH cells is put together.

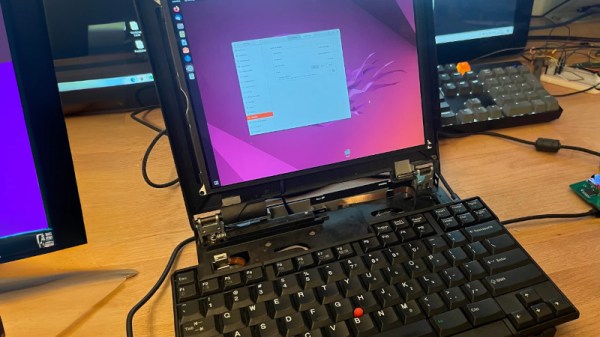

[polymatt] wanted this build to be as authentic as possible, so he even goes as far as replicating the label on the underside of the battery. With everything put together he has a faithful recreation of this decades-old battery for a famous retro laptop. ThinkPads are popular laptops in general, too, due to their fairly high build quality (at least for their enterprise lineups) and comprehensive driver support especially for Linux and other open-source software projects like coreboot and libreboot.

Thanks to [Roman UA] for the tip!

Continue reading “Reverse Engineering A Classic ThinkPad Battery”