XBMC (formerly Xbox Media Center) has always been a popular choice for retiring an original Xbox. Maybe people install it for lack of something better to do or maybe it’s the pride in having better media support than the 360. The XBMC team has found another device that has a pretty weak television experience, the Mac. Lifehacker took the latest XBMC for OSX beta build for a run now that it supports remote controls. It seems like a much more functional than Apple’s built in Front Row. There are a few things that don’t quite work yet, which you can find in the FAQ. We’re definitely going to try this on our old Mac mini… once we upgrade it to Leopard, which is an unfortunate caveat that might prevent people from running XBMC on legacy hardware. There is no Apple TV support planned because of limited horsepower and the hacking hurdles that might be required. If you’re interested in repurposing your old Xbox with XBMC, check out Lifehacker’s install guide.

An Open XBOX Modchip Enters The Scene

If you’ve ever bought a modchip that adds features to your game console, you might have noticed sanded-off IC markings, epoxy blobs, or just obscure chips with unknown source code. It’s ironic – these modchips are a shining example of hacking, and yet they don’t represent hacking culture one bit. Usually, they are more of a black box than the console they’re tapping into. This problem has plagued the original XBOX hacking community, having them rely on inconsistent suppliers of obscure boards that would regularly fall off the radar as each crucial part went to end of life. Now, a group of hackers have come up with a solution, and [Macho Nacho Productions] on YouTube tells us its story – it’s an open-source modchip with an open firmware, ModXO.

Like many modern modchips and adapters, ModXO is based on an RP2040, and it’s got a lot of potential – it already works for feeding a BIOS to your console, it’s quite easy to install, and it’s only going to get better. [Macho Nacho Productions] shows us the modchip install process in the video, tells us about the hackers involved, and gives us a sneak peek at the upcoming features, including, possibly, support for the Prometheos project that equips your Xbox with an entire service menu. Plus, with open-source firmware and hardware, you can add tons more flashy and useful stuff, like small LCD/OLED screens for status display and LED strips of all sorts!

If you’re looking to add a modchip to your OG XBOX, it looks like the proprietary options aren’t much worth considering anymore. XBOX hacking has a strong community behind it for historical reasons and has spawned entire projects like XBMC that outgrew the community. There’s even an amazing book about how its security got hacked. If you would like to read it, it’s free and worth your time. As for open-source modchips, they rule, and it’s not the first one we see [Macho Nacho Productions] tell us about – here’s an open GameCube modchip that shook the scene, also with a RP2040!

Using JTAG To Dump The Xbox’s Secret Boot ROM

When Microsoft released its first entry into the video game console market with the Xbox, a lot of the discussions at the time revolved around the fact that it used a nearly off-the-shelf Intel CPU and NVIDIA GPU solution. This made it quite different from the very custom consoles from Nintendo and Sony, and invited thoughts on running custom code on the x86 console. Although the security in the console was hacked before long, there were still some open questions, such as whether the secret boot ROM could have been dumped via the CPU’s JTAG interface. This is the question which [Markus Gaasedelen] sought to answer.

The reason why this secret code was originally dumped by intercepting it as it made its merry way from the South to the North Bridge (containing the GPU) of the Xbox was because Microsoft had foolishly left this path unencrypted, and because the JTAG interface on the CPU was left disabled via the TRST# pin which was tied to ground. This meant that without removing the CPU and adding some kind of interposer, the JTAG interface would not be active.

A small issue after the harrowing task of desoldering the CPU and reinstalling it with the custom interposer in place was to keep the system integrity check (enforced by an onboard PIC16 MCU) intact. With the CPU hooked up to the JTAG debugger this check failed, requiring an external injection of the signal on the I2C bus to keep the PIC16 from resetting the system. Yet even after all of this, and getting the secret bootrom code dumped via JTAG, there was one final system reset that was tied to the detection of an abnormal CPU start-up.

The original Xbox ended up being hacked pretty thoroughly, famously giving rise to projects like Xbox Media Center (XBMC), which today is known as Kodi. Microsoft learned their lesson though, as each of their new consoles has been more secure than the last. Barring some colossal screw-up in Redmond, the glory days of Xbox hacking are sadly well behind us.

The Mini Console Revolution, And Why Hackers Passed Them By

The Raspberry Pi was initially developed as an educational tool. With its bargain price and digital IO, it quickly became a hacker favorite. It also packed just enough power to serve as a compact emulation platform for anyone savvy enough to load up a few ROMs on an SD card.

Video game titans haven’t turned a blind eye to this, realising there’s still a market for classic titles. Combine that with the Internet’s love of anything small and cute, and the market was primed for the release of tiny retro consoles.

Often selling out quickly upon release, the devices have met with a mixed reception at times due to the quality of the experience and the games included in the box. With so many people turning the Pi into a retrogaming machine, these mini-consoles purpose built for the same should have been immediately loved by hardware hackers, right? So what happened?

Continue reading “The Mini Console Revolution, And Why Hackers Passed Them By”

Hackaday Celebrates 15 Years And Oh How The Hardware Has Changed

Today marks exactly 15 years since Hackaday began featuring one Hack a Day, and we’ve haven’t missed a day since. Over 5,477 days we’ve published 34,057 articles, and the Hackaday community has logged 903,114 comments. It’s an amazing body of work from our writers and editors, a humbling level of involvement from our readers, and an absolutely incredible contribution to open hardware by the project creators who have shared details of their work and given us all something to talk about and to strive for.

What began as a blog is now a global virtual hackerspace. That first 105-word article has grown far beyond project features to include spectacular long-form original content. From our community of readers has grown Hackaday.io, launched in 2014 you’ll now find over 30,000 projects published by 350,000 members. The same year the Hackaday Prize was founded as a global engineering initiative seeking to promote open hardware, offering big prizes for big ideas (and the willingness to share them). Our virtual connections were also given the chance to come alive through the Hackaday Superconference, Hackaday Belgrade, numerous Hackaday Unconferences, and meetups all over the world.

All of this melts together into a huge support structure for anyone who wants to float an interesting idea with a proof of concept where “why” is the wrong question. Together we challenge the limits of what things are meant to do, and collectively we filter through the best ideas and hold them high as building blocks for the next iteration. The Hackaday community is the common link in the collective brain, a validation point for perpetuating great ideas of old, and cataloging the ones of new.

Perhaps the most impressive thing about the last 15 years of Hackaday is how much the technological landscape has changed. Hackaday is still around because all of us have actively changed along with it — always looking for that cutting edge where the clever misuse of something becomes the base for the next transformative change. So we thought we’d take a look back 15 years in tech. Let’s dig into a time when there were no modules for electronics, you couldn’t just whip up a plastic part in an afternoon, designing your own silicon was unheard of, and your parts distributor was the horde of broken electronics in your back room.

Continue reading “Hackaday Celebrates 15 Years And Oh How The Hardware Has Changed”

How The Xbox Was Hacked

The millennium: a term that few had any use for before 1999, yet seemingly overnight it was everywhere. The turning of the millenium permeated every facet of pop culture. Unconventional popstars like Moby supplied electronica to the mainstream airwaves while audiences contemplated whether computers were the true enemy after seeing The Matrix. We were torn between anxiety — the impending Y2K bug bringing the end of civilization that Prince prophesied — and anticipation: the forthcoming release of the PlayStation 2.

Sony was poised to take control of the videogame console market once again. They had already sold more units of the original PlayStation than all of their competition combined. Their heavy cloud of influence over gamers meant that the next generation of games wasn’t going to start in until the PS2 was on store shelves. On the tail of Sony announcing the technical specs on their machine, rumors of a new competitor entering the “console wars” began to spread. That new competitor was Microsoft, an American company playing in a Japanese company’s game.

Continue reading “How The Xbox Was Hacked”

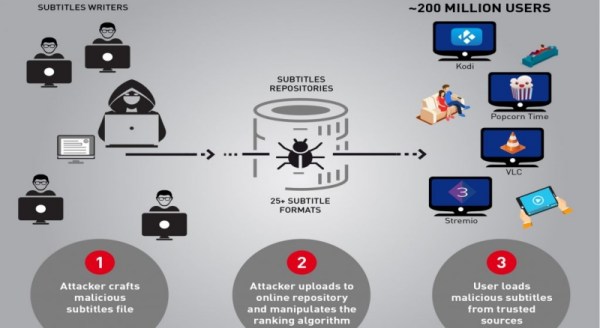

Hacked By Subtitles

CheckPoint researchers published in the company blog a warning about a vulnerability affecting several video players. They found that VLC, Kodi (XBMC), Popcorn-Time and strem.io are all vulnerable to attack via malicious subtitle files. By carefully crafting a subtitles file they claim to have managed to take complete control over any type of device using the affected players when they try to load a video and the respective subtitles.

According to the researchers, things look pretty grim:

We estimate there are approximately 200 million video players and streamers that currently run the vulnerable software, making this one of the most widespread, easily accessed and zero-resistance vulnerability reported in recent years. (…) Each of the media players found to be vulnerable to date has millions of users, and we believe other media players could be vulnerable to similar attacks as well.

One of the reasons you might want to make sure your software is up to date is that some media players download subtitles automatically from several shared online repositories. An attacker, as the researchers proved, could manipulate the website’s ranking algorithm and not only would entice more unsuspecting users to manually download his subtitles, but would also guarantee that his crafted malicious subtitles would be those automatically downloaded by the media players.

No additional details were disclosed yet about how each video player is affected, although the researchers did share the details to each of the software developers so they can tackle the issue. They reported that some of the problems are already fixed in their current versions, while others are still being investigated. It might be a good idea to watch carefully and update your system before the details come out.

Meanwhile, we can look at the trailer: