The concept of creating a gaming portable out of a home console has been around for some time, but it’s hardly seen the other way around. There have been a few devices that dared to straddle the line (i.e., Sega Nomad, Nintendo Switch, etc.), but the two worlds typically remain separate. [Stephen] looked to explore that space by attempting to turn the Game Boy Advance into a “big boy” console. The FPGA-based mod kit he created does just that, and comes complete with controller support and digital video output in 720p over a mini HDMI cable.

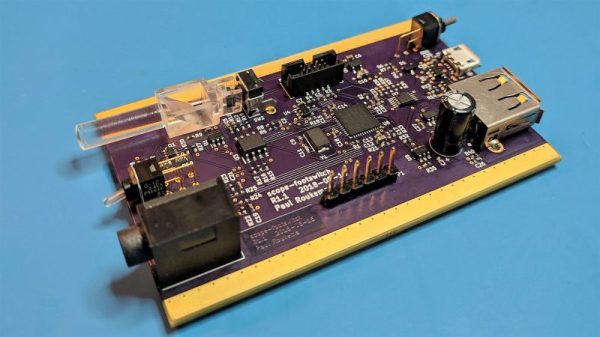

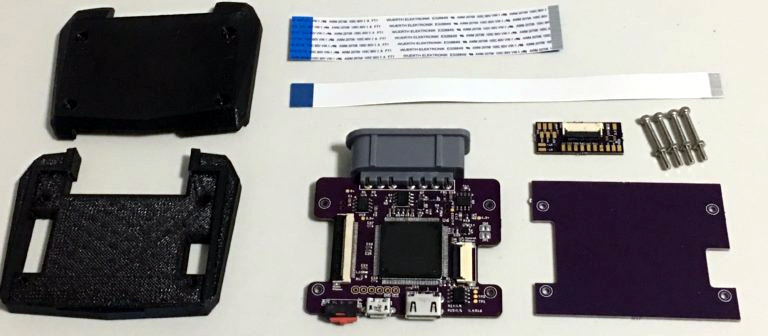

The kit itself was designed specifically for the original model GBAs containing the 40-pin LCD ribbon cable. These original models were the early run of non-backlit screens that are also denoted by a motherboard designation that can be seen by peering into the battery compartment. RGB signals are read directly from the GBA LCD socket by removing the handheld’s screen in favor of a fresh flat flex ribbon cable. This method enables a noise-free digital-to-digital solution as opposed to the digital-to-analog output of Nintendo’s own Game Boy Player add-on for the GameCube.

At an astonishing 240×160 native resolution, GBA video is scaled by the FPGA up to 5x within a 720p frame. Of course some of the image is cutoff in the process, so options for 4x and 4.5x scales were included. As a wise man once said, “Leave no pixel behind”. Since Nintendo designed the GBA clock to run at 59.7276 Hz, [Stephen] removed the oscillator crystal in order to sync the refresh rate to a more HDMI friendly 60 Hz. This means that the mod kit overclocks GBA games ever so slightly, though [Stephen] included a GBA cycle accurate mode as an option if your display can handle it.

The video below is [Stephen]’s initial test using a SNES controller. Tests must have gone well, because he decided to incorporate a SNES controller port in the final design. Now all those Super Nintendo ports on the GBA are back home once again thanks to this “consolizer” kit.

Continue reading “GBA On The Big Screen: FPGA Delivers HDMI And Every Feature Imaginable”