By now, everyone and their dog has at least heard of Bitcoin. While no government will accept tax payments in Bitcoin just yet, it’s ridiculously close to being real money. We’ve even paid for pizza delivery in Bitcoin. But it’s not the only cryptocurrency in town.

Ethereum initially launched in 2015 is an open source, it has been making headway among the 900 or so Bitcoin clones and is the number two cryptocurrency in the world, with only Bitcoin beating it in value. This year alone, the Ether has risen in value by around 4000%, and at time of writing is worth $375 per coin. And while the Bitcoin world is dominated by professional, purpose-built mining rigs, there is still room in the Ethereum ecosystem for the little guy or gal.

Ethereum is for Hackers

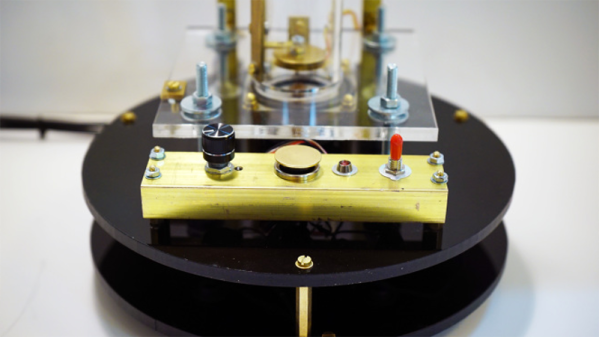

There may be many factors behind Ethereum’s popularity, however one reason is that the algorithm is designed to be resistant to ASIC mining. Unlike Bitcoin, anyone with a half decent graphics card or decent gaming rig can mine Ether, giving them the chance to make some digital currency. This is largely because mining Ethereum coins requires lots of high-speed memory, which ASICs lack. The algorithm also has built-in ASIC detection and will refuse to mine properly on them.

Small-scale Bitcoin miners were stung when the mining technology jumped from GPU to ASICs. ASIC-based miners simply outperformed the home gamer, and individuals suddenly discovered that their rigs were not worth much since there was a stampede of people trying to sell off their high-end GPU’s all at once. Some would go on to buy or build an ASIC but the vast majority just stopped mining. They were out of the game they couldn’t compete with ASICs and be profitable since mining in its self uses huge amounts of electricity.

Economies of scale like those in Bitcoin mining tend to favor a small number of very large players, which is in tension with the distributed nature of cryptocurrencies which relies on consensus to validate transactions. It’s much easier to imagine that a small number of large players would collude to manipulate the currency, for instance. Ethereum on the other hand hopes to keep their miners GPU-based to avoid huge mining farms and give the average Joe a chance at scoring big and discovering a coin on their own computer.

Ethereum Matters

Ethereum’s rise to popularity has basically undone Bitcoin’s move to ASICs, at least in the gamer and graphics card markets. Suddenly, used high-end graphics cards are worth something again. And there are effects in new equipment market. For instance, AMD cards seem to outperform other cards at the moment and they are taking advantage of this with their release of Mining specific GPU drivers for their new Vega architecture. Indeed, even though AMD bundled its hottest RX Vega 64 GPU with two games, a motherboard, and a CPU in an attempt to make the package more appealing to gamers than miners, AMD’s Radeon RX Vega 56 sold out in five minutes with Ethereum miners being blamed.

Besides creating ripples in the market for high-end gaming computers, cryptocurrencies are probably going to be relevant in the broader economy, and Ethereum is number two for now. In a world where even banks are starting to take out patents on blockchain technology in an attempt to get in on the action, cryptocurrencies aren’t as much of a fringe pursuit as they were a few years ago. Ethereum’s ASIC resistance is perhaps its killer feature, preventing centralization of control and keeping the little hacker in the mining game. Only time will tell if it’s going to be a Bitcoin contender, but it’s certainly worth keeping your eye on.