Technology is designed to serve us and make our lives better. When a device gets outdated, it is either disposed of or is buried in a pile of junk never to be seen again. However, some individuals tend to develop a certain respect for their mechanical servants and make an effort to preserve them long after they have become redundant.

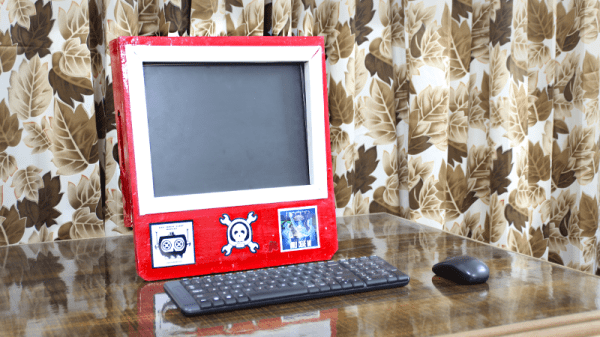

My relationship with my first laptop is a shining example of how to hold onto beloved hardware way too long. I converted that laptop into a desktop with a number of serious modifications which helped me learn about woodworking along the way. Maybe it’s more pragmatic to just buy new equipment. But you spend so much time each day using your devices. It is incredibly satisfying to have a personal connection that comes from pouring your own craftsmanship into them.

Why the Effort?

The laptop in question is an IBM R60 which I lugged around during the first three years after I graduated. It was my companion during some tough times and naturally, I developed a certain attachment to it. With time its peripherals failed including the keyboard which housed the power switch and it was decided that the cost of repair would outweigh its usefulness.

Then came the faithful day when I was inspired to make something with the scrap wood that had accumulated in my workshop. This would be my second woodworking project ever and I did not have the professional heavy machinery advertised in most YouTube videos. Yet I had two targets in mind with this project.

- Make the R60 useful again.

- Learn about woodworking for creating enclosures for future projects.

Armed with mostly hand tools, a drill and a grinder that was fitted with a saw blade, I started with the IBM R60 to all-in-one PC mod. Following is a log of things I did and those I regret not doing a.k.a. lessons learned. Read on.

Continue reading “Wooden Laptop Enclosure: New Life For Old Thinkpad”