The nuclear age changed steel, and for decades we had to pay the price for it. The first tests of the atomic bomb were a milestone in many ways, and have left a mark in history and in the surface of the Earth. The level of background radiation in the air increased, and this had an effect on the production of steel, so that steel produced since 1945 has had elevated levels of radioactivity. This can be a problem for sensitive instruments, so there was a demand for steel called low background steel, which was made before the trinity tests.

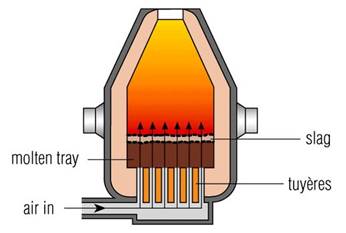

The production of steel is done with the Bessemer process, which takes the molten pig iron and blasts air through it. By pumping air through the steel, the oxygen reacts with impurities and oxidizes, and the impurities are drawn out either as gas or slag, which is then skimmed off. The problem is that the atmospheric air has radioactive impurities of its own, which are deposited into the steel, yielding a slightly radioactive material. Since the late 1960s steel production uses a slightly modified technique called the BOS, or Basic Oxygen Steelmaking, in which pure oxygen is pumped through the iron. This is better, but radioactive material can still slip through. In particular, we’re interested in cobalt, which dissolves very easily in steel, so it isn’t as affected by the Bessemer or BOS methods. Sometimes cobalt is intentionally added to steel, though not the radioactive isotope, and only for very specialized purposes.

Recycling is another reason that modern steel stays radioactive. We’ve been great about recycling steel, but the downside is that some of those impurities stick around.

Why Do We Need Low Background Steel?

Imagine you have a sensor that needs to be extremely sensitive to low levels of radiation. This could be Geiger counters, medical devices, or vehicles destined for space exploration. If they have a container that is slightly radioactive it creates an unacceptable noise floor. That’s where Low Background Steel comes in.

So where do you get steel, which is a man-made material, that was made before 1945? Primarily from the ocean, in sunken ships from WWII. They weren’t exposed to the atomic age air when they were made, and haven’t been recycled and mixed with newer radioactive steel. We literally cut the ships apart underwater, scrape off the barnacles, and reuse the steel.

Fortunately, this is a problem that’s going away on its own, so the headline is really only appropriate as a great reference to a popular movie. After 1975, testing moved underground, reducing, but not eliminating, the amount of radiation pumped into the air. Since various treaties ending the testing of nuclear weapons, and thanks to the short half-life of some of the radioactive isotopes, the background radiation in the air has been decreasing. Cobalt-60 has a half-life of 5.26 years, which means that steel is getting less and less radioactive on its own (Cobalt-60 from 1945 would now be at .008% of original levels). The newer BOS technique exposes the steel to fewer impurities from the air, too. Eventually the need for special low background steel will be just a memory.

Fortunately, this is a problem that’s going away on its own, so the headline is really only appropriate as a great reference to a popular movie. After 1975, testing moved underground, reducing, but not eliminating, the amount of radiation pumped into the air. Since various treaties ending the testing of nuclear weapons, and thanks to the short half-life of some of the radioactive isotopes, the background radiation in the air has been decreasing. Cobalt-60 has a half-life of 5.26 years, which means that steel is getting less and less radioactive on its own (Cobalt-60 from 1945 would now be at .008% of original levels). The newer BOS technique exposes the steel to fewer impurities from the air, too. Eventually the need for special low background steel will be just a memory.

Oddly enough, steel isn’t the only thing that we’ve dragged from the bottom of the ocean. Ancient Roman lead has also had a part in modern sensing.