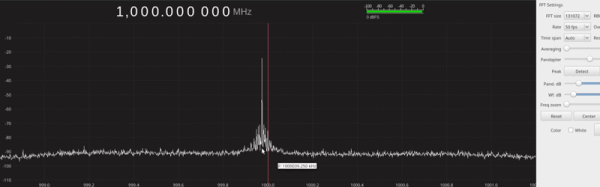

How hard is it to create a synthesizer to generate frequencies between 35 MHz to 4.4 GHz? [OpenTechLab] noticed a rash of boards based on the ADF4351 that could do just that priced at under $30. He decided to get one and try it out and you can find his video results below.

At that price point, he didn’t expect much from it, but he did want to experiment with it to see if he could use it as an inexpensive piece of test gear. The video is quite comprehensive (and weighs in at nearly an hour and a half). It covers not just the device from a software and output perspective but also talks about the theory behind these devices. [OpenTechLab] even sniffed the USB connection to find the protocol used to talk to the device. He wasn’t overly impressed with the performance of the board but was happy enough with the results at the price and he plans to make some projects with it.