What do you do with a cool-looking misfit guitar that has non-working built-in effects and some iffy design aspects? Do you try to fix it and keep it original, or do you gut it and strut your stuff with new bits from around the shop? This is the conundrum that [Tim Sway] finds himself in with this late 70s/early 80s Formanta Solo II straight out of the USSR. (Video, embedded below.)

[Tim] likes a lot of things about it (and we do, too), especially the acid green pick guard, the sparkly pickups, and the beefy bridge that lets him set the string spacing individually, on the fly. It even has a built-in phaser and distortion, but those aren’t working and may never have worked that well at all.

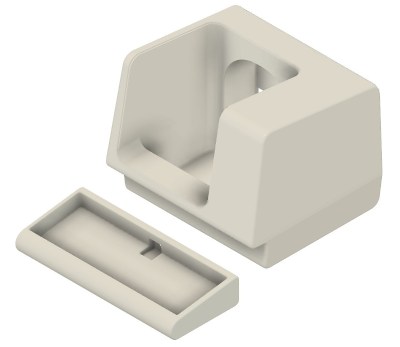

As you can see in the video below, [Tim] has already spent a few hours making it playable and a little more palatable in order to figure out what to do with it electronics-wise. He started by making the 9 V compartment big enough to actually fit a battery inside, and drilled out bigger holes for new tuners.

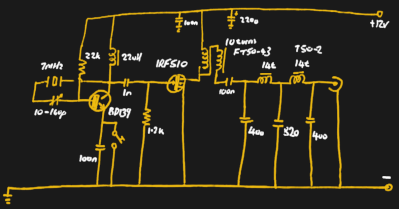

Interestingly, these guitars had a 5-pin DIN receptacle instead of a 1/4″ jack. [Tim] bought an adapter just in case, but once someone dug up a schematic and sent it over, he decided to rewire it with a 1/4″.

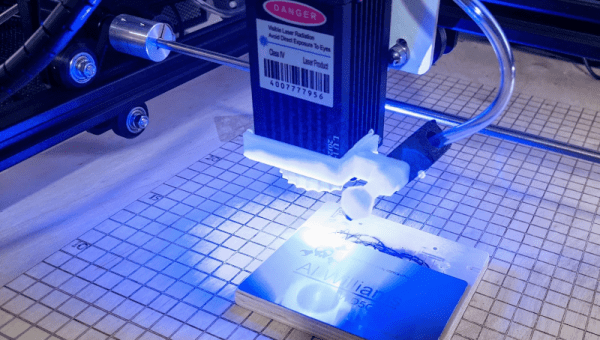

For all of its plus sides, [Tim] doesn’t like the headstock on this thing at all and found the neck to be too chunky for the modern guitarist, so he cut down the headstock, shaved down the neck a bit, and stained it dark. He also made a new nut out of what looks like rosewood. Then it was on to the more standard stuff — file down the frets and polish them, oil the fretboard, and clean up the body.

The point of this exercise is to make a usable guitar for the modern musician. As [Tim] says, this is not a particularly valuable guitar, nor is it rare, and it wasn’t built that well to begin with. One of the issues is the switches — they’re kind of light and cheesy feeling, and one of them is directly in the strum path. Will [Tim] change those out but fix the original effects, or will he make the thing completely his own? We wait with bated breath.

Want to mess around with cheap old guitars, but don’t know where to start? Our own [Sven Gregori] has your back with Axe Hacks.

Via adafruit