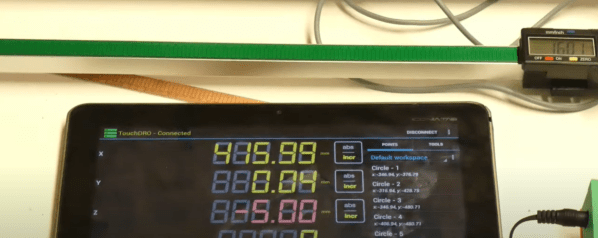

The working principle of digital calipers is mysterious enough that we’d never think to dismantle, much less improve them, right? Well, think again, as [Limi DIY] retrofits the processing element onto a custom track, extending the calipers measurement distance to a whopping 650 mm. Combined with a prior project to extract the measurement data, the result makes for a working multi-axis digital readout, a handy device for machine tools like a manual lathe or milling machine.

Digital calipers operate on the principle of measuring an array of variable capacitors. If we scratch our heads and look back at our physics notes, we’ll recall that the capacitance between two parallel conductive plates is linearly proportional to the surface area. By fixing one dimension of both plates and by sliding one plate over the other, we effectively change the area, giving ourselves a simple linear displacement sensor! (There are some classy error-correcting techniques too, and this [PDF] is a great place to look for more details.)

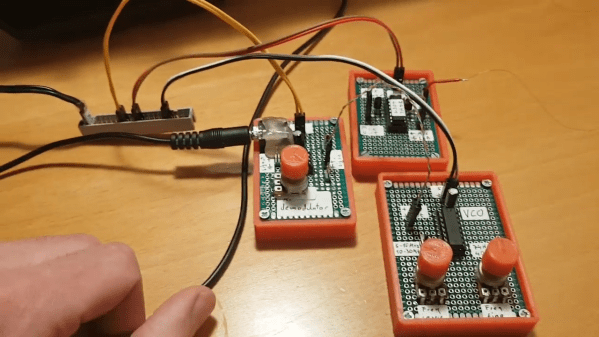

The theory takeaway is that this array of parallel plates can be embedded directly into a printed circuit board. We just need to know the dimensions. After some close measurement work, [Limi DIY] extracted the crucial measurements and fabbed a PCB with the pattern duplicated over 650 mm. After retrofitting the original processing element onto this new track, they had a working measurement device that’s far longer than the original!

If you’ve ever been tempted to disassemble your calipers but too nervous to bite off the investment, now’s your chance to follow along as [Lima DIY] demonstrates the gratuitous disassembly process for you in video format. And the fruits of their labor is also captured on a project post that includes the key dimensions if you’re looking to do the same thing.

If you’re looking for other ways to improve your calipers, why not start by giving them a major battery life boost.

Thanks to [absd] via [Jubilee Discord] for the tip!

Continue reading “Custom Caliper Tracks For When You’re Going The Distance”