A large part of the world still educates their kids using a system that’s completely antiquated. Personal choices and interests don’t matter, and learning by rote is the norm. Government schooling is woefully inadequate and the teachers are just not equipped, or trained, to be able to impart useful education. [Arvind Gupta], a science educator, is trying to change this by teaching kids how to build toys. His YouTube channel on Toys for Science and Math Education has almost 100,000 subscribers and over 44 million views. It’s awesome.

[Arvind] graduated from one of the finest engineering schools in India, the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, and joined the TATA conglomerate at their heavy-vehicles plant helping build trucks. It didn’t take him long to realize that he wasn’t cut out to be building trucks. So he took a year off and enrolled in a village science program which was working towards changing the education system. At the weekly village bazaar, he came across interesting pieces of arts and crafts that the villagers were selling. A piece of rubber tubing, used as the core of the valve in bicycle tubes, caught his eye. He bought a length and a couple of matchboxes, and created what he calls “matchstick Meccano”.

[Arvind] graduated from one of the finest engineering schools in India, the Indian Institute of Technology in Kanpur, and joined the TATA conglomerate at their heavy-vehicles plant helping build trucks. It didn’t take him long to realize that he wasn’t cut out to be building trucks. So he took a year off and enrolled in a village science program which was working towards changing the education system. At the weekly village bazaar, he came across interesting pieces of arts and crafts that the villagers were selling. A piece of rubber tubing, used as the core of the valve in bicycle tubes, caught his eye. He bought a length and a couple of matchboxes, and created what he calls “matchstick Meccano”.

This was in the 1970’s. Since then, he has been travelling all over India getting children to learn by building fun toys. The toys he designs are made from commonly available raw material and can be easily built with minimum resources. These ingenious DIY toys and activities help make maths and science education fun and interesting for children at all levels of schooling. All of his work is shared in the spirit of open source and available via his website and YouTube channels. A large body of his work has been translated in to almost 20 languages and you are welcome to help add to that list by dubbing the videos.

Check out the INK Conference video below where he shares his passion for education and shows simple yet entertaining and well-designed toys built from trash and recycled materials.

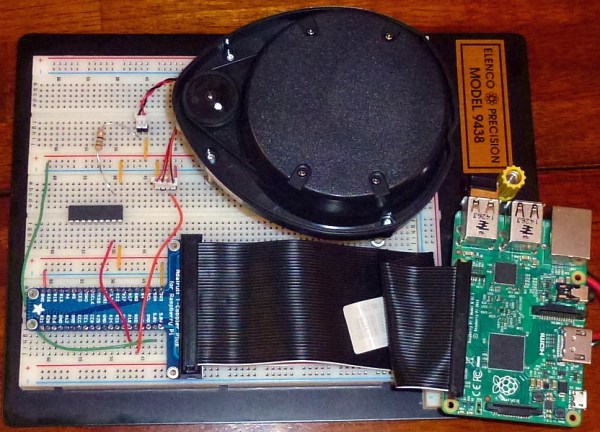

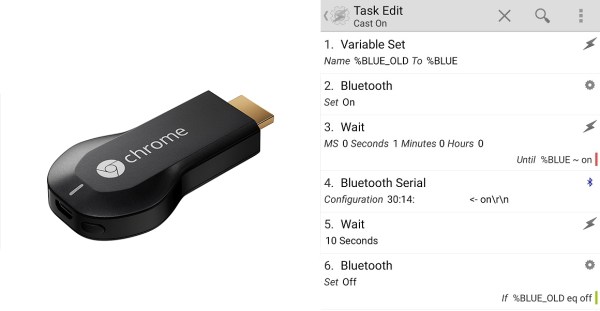

Now in all honesty, the Chromecast gets hot but the amount of power it draws when not in use is still pretty negligible compared to the draw of your TV. Every watt counts, and [Ilias] took this as an opportunity to refine his skills and combine a system using an Arduino, Bluetooth, and Android to create a robust power switch solution for the Chromecast.

Now in all honesty, the Chromecast gets hot but the amount of power it draws when not in use is still pretty negligible compared to the draw of your TV. Every watt counts, and [Ilias] took this as an opportunity to refine his skills and combine a system using an Arduino, Bluetooth, and Android to create a robust power switch solution for the Chromecast.

Once you consider all the possible orders in which you place the pieces, it becomes ridiculously computationally expensive, so SVGnest cheats and uses a

Once you consider all the possible orders in which you place the pieces, it becomes ridiculously computationally expensive, so SVGnest cheats and uses a