Stumbling around YouTube, we found what has to be the lowest-tech method of producing a touchpad to make a capacitive touch keyboard, and we just had to share it with you. If you’re afraid of spoilers, skip down to the video below the break now.

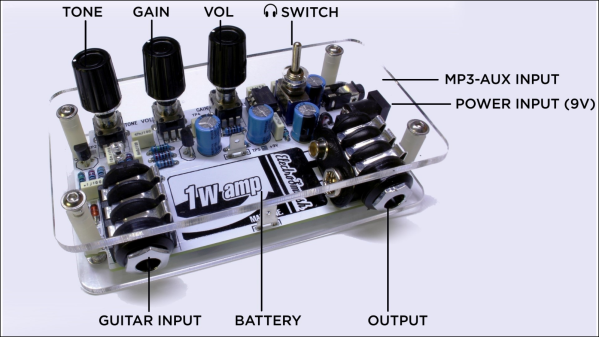

[James Eckert] got his hands on a Freescale MPR121 capacitive touch sensor. The chip in question speaks I2C and senses up to twelve simultaneous capacitive sense electrodes; break-out boards are available in all of the usual places. It’s a sweet little part.

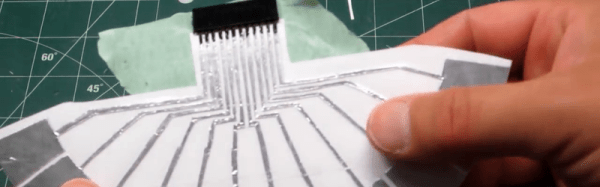

So [James] had to make a twelve-key capacitive keyboard on the quick. He printed out a key template on paper — something that he does often in his woodwork — and spray-glued aluminum foil on the back side. The video doesn’t say how many hours he spent with the razor blade tracing it all out, but the result is a paper, foil, and packing tape keyboard that seems to work just fine.

A pin-header was affixed to the foil with conductive paint and more tape. If you’ve ever tried soldering directly to aluminum foil, you’d know why. (And if you’ve got any other good tips for connecting electrically to aluminum foil, we’d love to hear them.)

Continue reading “Conjuring Capacitive Touch Sensors From Paper And Aluminum Foil”