There are a lot of projects in the Hackaday Prize aimed at improving the lives of those of us who are disabled or otherwise handicapped. A good 3D printed prosthetic is a natural idea for the competition, as are projects for the blind and deaf. [Patrick Joyce], [Steve Evans] and [David Hopkinson] are helping a much more debilitating disease: Motor Neuron Disease, or ALS. [Steve] and [Patrick] both have ALS, and they’re working on a project that will use the movement of their eyes to move their wheelchair.

The project began as an idea [Patrick] had a few years ago – why not use commercial eye tracking technology to drive a wheelchair. Eye tracking technology is a reasonably well-solved problem but for some inexplicable reason there are no clear ways to connect this system to a wheelchair.

Over the last few years, [Patrick] taught himself Arduino and Processing to prototype a device that would connect to a computer running an eye tracking tool and to translate this into servo movements. A small 3D printed contraption is connected to the joystick of [Patrick]’s wheelchair, and with just a little bit more code, he can drive his wheelchair around just by looking at a screen. It’s a great use of 3D printing and the humble Arduino, but it’s absolutely impressive this technology hasn’t existed before.

Because [Patrick] can build pretty much whatever hardware he wants, he’s also added a few neat features. The ‘Brain Box’ for this build needs two outputs for servos, but [Patrick] added two more for other purposes. He’ll be mounting a Nerf blaster to the side of his chair, but he also has other ideas of adding a fan, a robot arm, or even IR or RF transmitters; he’ll be able to control his TV with just his eyes.

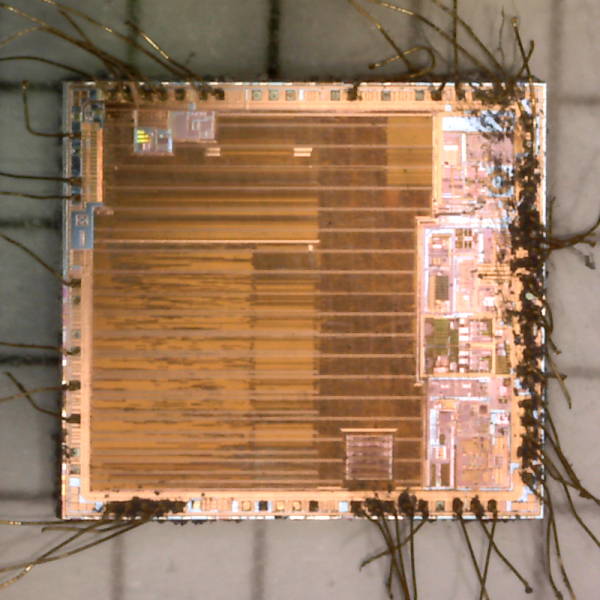

[Jelmer] was curious to know if the price difference was all in the software. And in order to verify this decided that decapping was the only thing to do!

[Jelmer] was curious to know if the price difference was all in the software. And in order to verify this decided that decapping was the only thing to do!