USB-C is one of those things that generally everyone seems to agree on that it is a ‘good thing’, but is it really? In this first part of a series on USB-C, [Andreas Spiess] takes us through the theory of USB-C and USB Power Delivery (PD), as well as data transfer with USB-C cables. Even ignoring the obvious conclusion that with USB-C USB should now actually be called the ‘Universal Parallel Bus’ on account of its two pairs of differential data lines, there’s quite a bit of theory and associated implementation details involved.

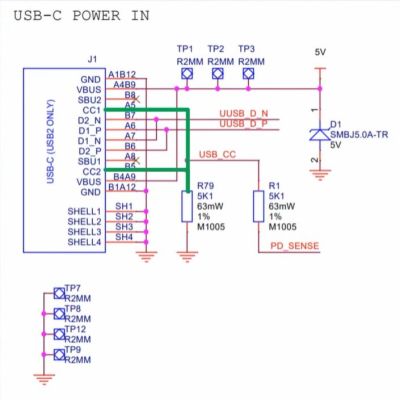

Starting with the USB 2.0 ‘legacy mode’ and the very boring and predictable 5 V power delivery in this mode, [Andreas] shows why you may not get any power delivered to a device with USB-C connector. Most likely the Downstream Facing Peripheral (DFP, AKA not the host) lacks the required resistors on the CC (Configuration Channel) pins, which are both what the other USB-C end uses to determine the connector orientation, as well as what type of device is connected.

This is where early Raspberry Pi 4B users for example saw themselves caught by surprise when their boards didn’t power up except with some USB cables.

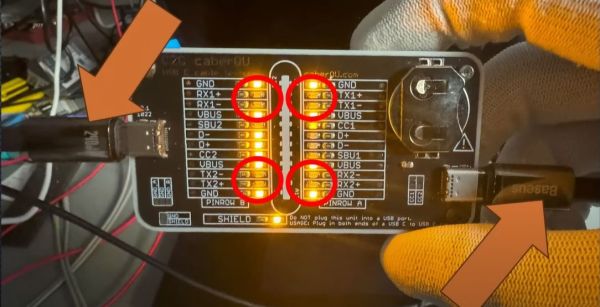

The saga continues through [Andreas]’s collection of USB-C cables, as he shows that many of them lack the TX/RX pairs, and that’s before trying to figure out which cables have the e-marker chip to allow for higher voltages and currents.

On the whole we’re still excited about what USB-C brings to the table, but the sheer complexity and number of variables make that there are a myriad of ways in which something cannot work as expected. Ergo Caveat Emptor.

Continue reading “Getting Started With USB-C And Common Pitfalls With Charging And Data Transfer”

![The nearly final measurement by [Double M Innovations].](https://hackaday.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/hv_transmission_line_energy_harvesting_final_count.jpg?w=400)