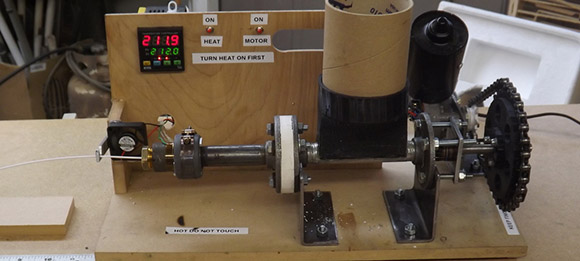

When you’re getting close to a production run the prototypes really need to hit the mark before pulling the trigger. [Bob’s] still hard at work getting his scoreboard off the ground and his most recent endeavor was to find a way to prototype the rubber gasket without blowing his shoestring budget. His solution was to harness the power of 3D printing to generate a model from which he could create the mold from which he cast the rubber part.

To make things a bit more difficult, the band isn’t just decorative, it doubles as the tactile part of the scoreboard buttons. You can see all six of them (before being painted to make them stand out) in the inset image above. Just above that image is a picture of the mold making process. The toothpicks are suspending the 3D printed model of the rubber band while the lower half of the silicone mold sets up. Once that had happened [Bob] sprayed release agent to ensure the top half of the mold wouldn’t stick while it cured.

The results turned out just great. Sure, this isn’t the way to go if you’re making a lot of these things. But we’re impressed at the quality he achieve for a one-off item.

If the finished product on the left looks familiar it’s because we looked in on the project last June. [Bob] continues with improvements and plans to launch a crowd funding campaign this week.