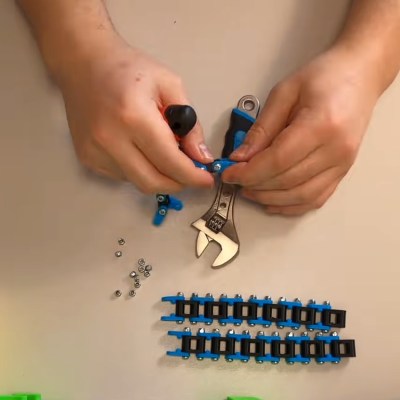

T-slot extrusions used to be somewhat mysterious, but today they are quite common thanks to their use in many 3D printers. However, it is one thing to assemble a kit with some extrusions and another thing to design your own creations with the material. If you ever had a Play-Doh Fun Factory as a kid, then you know about extrusions. You push some material out through a die to make a shape. Of course, aluminum extrusions aren’t made from modeling clay, but usually 6105-T5 aluminum. Oddly, there doesn’t seem to be an official standard, but it is so common that there’s usually not much variation between different vendors.

We use extrusions to create frames for 3D printers, laser cutters, and CNC machines. But you can use it anywhere you need a sturdy and versatile frame. There seems to be a lot of people using them, for example, to build custom fixtures inside vans. If you need a custom workbench, a light fixture, or even a picture frame, you can build anything you like using extrusions. Continue reading “Getting Started With Aluminum Extrusions”