As the art of 3D printing has refined itself over the years, a few accessories have emerged to take prints to the next level. One of them is the threaded insert, a a piece of machined brass designed to be heat-set into a printed hole in the part. They can be placed by hand with a soldering iron, or for the really cool kids, with a purpose-built press. They look great and they can certainly make assembly of a 3D printed structure very easy, but I’m here to tell you they are not as necessary as they might seem. There’s an alternative I have been using for years which does essentially the same job without the drama. Continue reading “No Need For Inserts If You’re Prepared To Use Self-Tappers”

3d Printer hacks2785 Articles

Watch Bondo Putty Get Sprayed Onto 3D Prints

3D prints destined for presentation need smooth surfaces, and that usually means sanding. [Uncle Jessy] came across an idea he decided to try out for himself: spraying Bondo spot putty onto a 3D print. Bondo spot putty comes from a tube, cures quickly, and sands smoothly. It’s commonly used to hide defects and give 3D prints a great finish. Could spraying liquified Bondo putty onto a 3D print save time, or act as a cheat code for hiding layer lines? [Uncle Jessy] decided to find out.

The first step is to turn the distinctive red putty into something that can be sprayed through a cheap, ten dollar airbrush. That part was as easy as squeezing putty into a cup and mixing in acetone in that-looks-about-right proportions. A little test spray showed everything working as expected, so [Uncle Jessy] used an iron man mask (smooth surfaces on the outside, textured inside) for a trial run.

Spraying the liquified Bondo putty looks about as easy as spraying paint. The distinctive red makes it easy to see coverage, and it cures very rapidly. It’s super easy to quickly give an object an even coating — even in textured and uneven spots — which is an advantage all on its own. To get a truly smooth surface one still needs to do some sanding, but the application itself looks super easy.

Is it worth doing? [Uncle Jessy] says it depends. First of all, aerosolizing Bondo requires attention to be paid to safety. There’s also a fair bit of setup involved (and a bit of mess) so it might not be worth the hassle for small pieces, but for larger objects it seems like a huge time saver. It certainly seems to cover layer lines nicely, but one is still left with a Bondo-coated object in the end that might require additional sanding, so it’s not necessarily a cheat code for a finished product.

If you think the procedure might be useful, check out the video (embedded below) for a walkthrough. Just remember to do it in a well-ventilated area and wear appropriate PPE.

An alternative to applying Bondo is brush application of UV resin, but we’ve also seen interesting results from non-planar ironing.

Continue reading “Watch Bondo Putty Get Sprayed Onto 3D Prints”

Does It Make Sense To Upgrade A Prusa MK4S To A Core One?

One of the interesting things about Prusa’s FDM 3D printers is the availability of official upgrade kits, which allow you to combine bits off an older machine with those of the target machine to ideally save some money and not have an old machine gathering dust after the upgrade. While for a bedslinger-to-bedslinger upgrade this can make a lot of sense, the bedslinger to CoreXY Core One upgrade path is a bit more drastic. Recently the [Aurora Tech] channel had a look at which upgrade path makes the most sense, and in which scenario.

A big part of the comparison is the time and money spent compared to the print result, as you have effectively four options. Either you stick with the MK4S, get the DIY Core One (~8 hours of assembly time), get the pre-assembled Core One (more $$), or get the upgrade kit (also ~8 hours). There’s also the fifth option of getting the enclosure for the MK4S, but it costs about as much as the upgrade kit, so that doesn’t make a lot of logical sense.

A big part of the comparison is the time and money spent compared to the print result, as you have effectively four options. Either you stick with the MK4S, get the DIY Core One (~8 hours of assembly time), get the pre-assembled Core One (more $$), or get the upgrade kit (also ~8 hours). There’s also the fifth option of getting the enclosure for the MK4S, but it costs about as much as the upgrade kit, so that doesn’t make a lot of logical sense.

In terms of print quality, it’s undeniable that the CoreXY motion system provides better results, with less ringing and better quality with tall prints, but unless you’re printing more than basic PLA and PETG, or care a lot about the faster print speeds of the CoreXY machine with large prints, the fully enclosed Core One is a bit overkill and sticking with the bedslinger may be the better choice.

The long and short of it is that you have look at each option and consider what works best for your needs and your wallet.

Continue reading “Does It Make Sense To Upgrade A Prusa MK4S To A Core One?”

PVDF: The Specialized Filament For Chemical And Moisture Resistance

There’s a dizzying number of specialist 3D printing materials out there, some of which do try to offer an alternative to PLA, PA6, ABS, etc., while others are happy to stay in their own niche. Polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) is one of these materials, with the [My Tech Fun] YouTube channel recently getting sent a spool of PVDF for testing, which retails for a cool $188.

Reading the specifications and datasheet for the filament over at the manufacturer’s website it’s pretty clear what the selling points are for this material are. For the chemists in the audience the addition of fluoride is probably a dead giveaway, as fluoride bonds in a material tend to be very stable. Hence PVDF ((C2H2F2)n) sees use in applications where strong resistance to aggressive chemicals as well as hydrolysis are a requirement, not to mention no hygroscopic inclinations, somewhat like PTFE and kin.

In the video’s mechanical testing it was therefore unsurprising that other than abrasion resistance it’s overall worse and more brittle than PA6 (nylon). It was also found that printing this material with two different FDM printers with the required bed temperature of 110°C was somewhat rough, with some warping and a wrecked engineering build plate in the Bambu Lab printer due to what appears to be an interaction with the usual glue stick material. Once you get the print settings dialed in it’s not too complicated, but it’s definitely not a filament for casual use.

Continue reading “PVDF: The Specialized Filament For Chemical And Moisture Resistance”

A Tool-changing 3D Printer For The Masses

Modern multi-material printers certainly have their advantages, but all that purging has a way to add up to oodles of waste. Tool-changing printers offer a way to do multi-material prints without the purge waste, but at the cost of complexity. Plastic’s cheap, though, so the logic has been that you could never save enough on materials cost to make up for the added capital cost of a tool-changer — that is, until now.

Currently active on Kickstarter, the Snapmaker U1 promises to change that equation. [Albert] got his hands on a pre-production prototype for a review on 247Printing, and what we see looks promising.

The printer features the ubiquitous 235 mm x 235 mm bed size — pretty much the standard for a printer these days, but quite a lot smaller than the bed of what’s arguably the machine’s closest competition, the tool-changing Prusa XL. On the other hand, at under one thousand US dollars, it’s one quarter the price of Prusa’s top of the line offering. Compared to the XL, it’s faster in every operation, from heating the bed and nozzle to actual printing and even head swapping. That said, as you’d expect from Prusa, the XL comes dialed-in for perfect prints in a way that Snapmaker doesn’t manage — particularly for TPU. You’re also limited to four tool heads, compared to the five supported by the Prusa XL.

The U1 is also faster in multi-material than its price-equivalent competitors from Bambu Lab, up to two to three times shorter print times, depending on the print. It’s worth noting that the actual print speed is comparable, but the Snapmaker takes the lead when you factor in all the time wasted purging and changing filaments.

The assisted spool loading on the sides of the machine uses RFID tags to automatically track the colour and material of Snapmaker filament. That feature seems to take a certain inspiration from the Bambu Labs Mini-AMS, but it is an area [Albert] identifies as needing particular attention from Snapmaker. In the beta configuration he got his hands on, it only loads filament about 50% of the time. One can only imagine the final production models will do better than that!

In spite of that, [Albert] says he’s backing the Kickstarter. Given Snapmaker is an established company — we featured an earlier Snapmaker CNC/Printer/Laser combo machine back in 2021— that’s less of a risk than it could be.

Continue reading “A Tool-changing 3D Printer For The Masses”

RepRapMicron Promises Micro-fabrication For Desktops With New Prototype

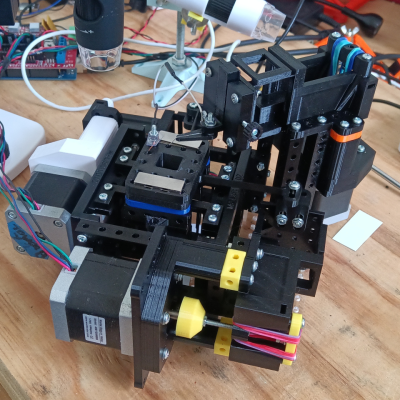

3D printing has transformed how hobbyists fabricate things, but what additional doors would open if we could go even smaller? The µRepRap (RepRapMicron) project aims to bring fabrication at the micron and sub-micron scale to hobbyists the same way RepRap strove to make 3D printing accessible. New developments by [Vik Olliver] show a promising way forward, and also highlight the many challenges of going so small.

How exactly would a 3D printer do micro-fabrication? Not by squirting plastic from a nozzle, but by using a vanishingly tiny needle-like effector (which can be made at any workbench via electrochemical erosion) to pick up a miniscule amount of resin one dab a time, curing it with UV after depositing it like a brush deposits a dot of ink.

By doing so repeatedly and in a structured way, one can 3D print at a micro scale one “pixel” (or voxel, more accurately) at a time. You can see how small they’re talking in the image in the header above. It shows a RepRapMicron tip (left) next to a 24 gauge hypodermic needle (right) which is just over half a millimeter in diameter.

Moving precisely and accurately at such a small scale also requires something new, and that is where flexures come in. Where other 3D printers use stepper motors and rails and belts, RepRapMicron leverages work done by the OpenFlexure project to achieve high-precision mechanical positioning without the need for fancy materials or mechanisms. We’ve actually seen this part in action, when [Vik Olliver] amazed us by scribing a 2D micron-scale Jolly Wrencher 1.5 mm x 1.5 mm in size, also visible in the header image above.

Using a tiny needle to deposit dabs of UV resin provides the platform with a way to 3D print, but there are still plenty of unique problems to be solved. How does one observe such a small process, or the finished print? How does one handle such a tiny object, or free it from the build platform without damaging it? The RepRapMicron project has solutions lined up for each of these and more, so there’s a lot of discovery waiting to be done. Got ideas of your own? The project welcomes collaboration. If you’d like to watch the latest developments as they happen, keep an eye on the Github repository and the blog.

CAL 3D Printing Spins Resin Right Round, Baby

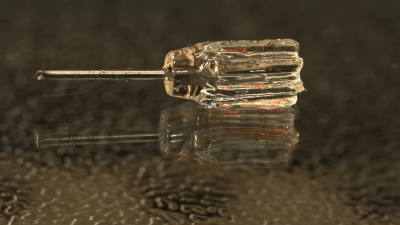

Computed Axial Lithography (CAL) is a lighting-fast form of volumetric 3D printing that holds incredible promise for the future, and [The Action Lab] filmed it in action at a Berkeley team’s booth at the “Open Sauce” convention.

The basic principle works like this: an extra-viscous photopolymer resin sits inside a rotating, transparent cylinder. As the cylinder rotates, UV light is projected into the resin in patterns carefully calculated to reproduce the object being printed. There are no layers, no FEP, and no stop-and-start; it’s just one long exposure from what is effectively an object-generating video, and it does not take long at all. You can probably guess that the photo above shows a Benchy being created, though unfortunately, we’re not told how long it took to produce.

Don’t expect to grab a bottle of SLA resin to get started: not only do you need higher viscosity, but also higher UV transmission than you get from an SLA resin to make this trick work. Like regular resin prints, the resolution can be astounding, and this technique even allows you to embed objects into the print.

It’s not a new idea. Not only have we covered CAL before, we even covered it being tested in zero-G. Floating in viscous resin means the part couldn’t care less about the local gravity field. What’s interesting here is that this hardware is at tabletop scale, and looks very much like something an enterprising hacker might put together.

Indeed, the team at Berkeley have announced their intention to open-source this machine, and are seeking to collaborate with the community on their Discord server. Hopefully we’ll see something more formally “open” in the future, as it’s something we’d love to dig deeper into — and maybe even build for ourselves.

Thanks to [Beowulf Shaeffer] for the tip. If you are doing something interesting with photopolymer ooze (or anything else) don’t hesitate to let us know! Continue reading “CAL 3D Printing Spins Resin Right Round, Baby”