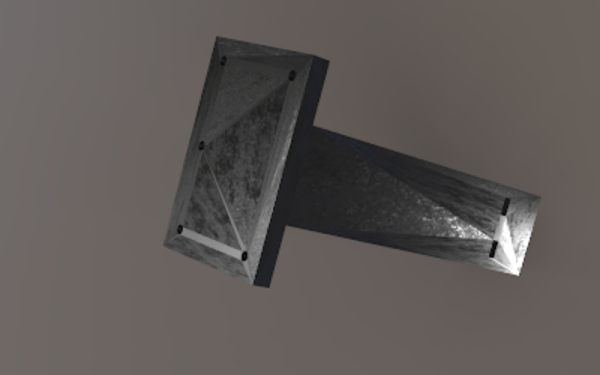

[Tommy]’s POLY555 is an analog, 20-note polyphonic synthesizer that makes heavy use of 3D printing and shows off some clever design. The POLY555, as well as [Tommy]’s earlier synth designs, are based around the 555 timer. But one 555 is one oscillator, which means only one note can be played at a time. To make the POLY555 polyphonic, [Tommy] took things to their logical extreme and simply added multiple 555s, expanding the capabilities while keeping the classic 555 synth heritage.

The real gem here is [Tommy]’s writeup. In it, he explains the various design choices and improvements that went into the POLY555, not just as an instrument, but as a kit intended to be produced and easy to assemble. Good DFM (Design For Manufacturability) takes time and effort, but pays off big time even for things made in relatively small quantities. Anything that reduces complexity, eliminates steps, or improves reliability is a change worth investigating.

The real gem here is [Tommy]’s writeup. In it, he explains the various design choices and improvements that went into the POLY555, not just as an instrument, but as a kit intended to be produced and easy to assemble. Good DFM (Design For Manufacturability) takes time and effort, but pays off big time even for things made in relatively small quantities. Anything that reduces complexity, eliminates steps, or improves reliability is a change worth investigating.

For example, the volume wheel is not a thumbwheel pot. It is actually a 3D-printed piece attached to the same potentiometer that the 555s use for tuning; meaning one less part to keep track of in the bill of materials. It’s all a gold mine of tips for anyone looking at making more than just a handful of something, and a peek into the hard work that goes into designing something to be produced. [Tommy] even has a short section dedicated to abandoned or rejected ideas that didn’t make the cut, which is educational in itself. Want more? Good news! This isn’t the first time we’ve been delighted with [Tommy]’s prototyping and design discussions.

POLY555’s design files (OpenSCAD for enclosure and parts, and KiCad for schematic and PCB) as well as assembly guide are all available on GitHub, and STL files can be found on Thingiverse. [Tommy] sells partial and complete kits as well, so there’s something for everyone’s comfort level. Watch the POLY555 in action in the video, embedded below.

Continue reading “Peek Into This Synth’s Great Design (And Abandoned Features)” →