Just about any 3D printer can be satisfying to watch as it works, but delta-style printers are especially hypnotic. There’s just something about the way that three linear motions add up to all kinds of complex shapes; it’s mesmerizing. Deltas aren’t without their problems, though, which led [Bruno Schwander] to undertake a trio of interesting mods on his Anycubic Kossel.

First up was an effort to reduce the mass of the business end of the printer, which can help positional accuracy and repeatability. This started with replacing the stock hot-end with a smaller, lighter MQ Mozzie, but that led to cooling problems that [Bruno] addressed with a ridiculously overpowered brushless hairdryer fan. The fan expects a 0 to 5-VDC signal for the BLDC controller, which meant he had to build an adapter to allow Marlin’s 12-volt PWM signal to control the fan.

Once the beast of a fan was tamed, [Bruno] came up with a clever remote mount for it. A 3D-printed shroud allowed him to mount the fan and adapter to the frame of the printer, with a flexible duct connecting it to the hot-end. The duct is made from lightweight nylon fabric with elastic material sewn into it to keep it from taut as the printhead moves around, looking a bit like an elephant’s trunk.

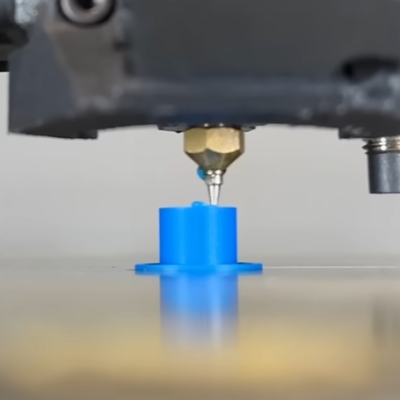

Finally, to solve his pet peeve of setting up and using the stock Z-probe, [Bruno] turned the entire print bed into a strain-gauge sensor. This took some doing, which the blog post details nicely, but it required building a composite spacer ring for the glass print bed to mount twelve strain gauges that are read by the venerable HX711 amplifier and an Arduino, which sends a signal to Marlin when the head touches the bed. The video below shows it and the remote fan in action.

Continue reading “Trio Of Mods Makes Delta Printer More Responsive, Easier To Use”