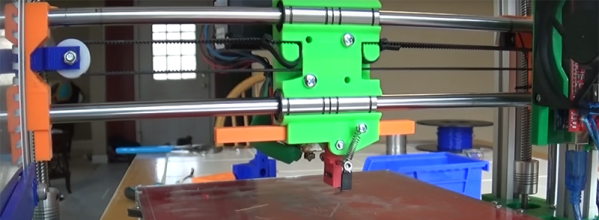

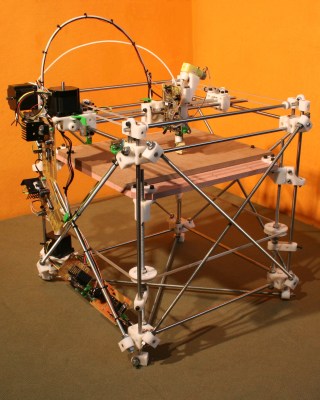

The beginning of the DIY 3D printing movement was a heady time. There was a vision of a post-scarcity world in which everything could and would be made at home, for free. Printers printing other printers would ensure the exponential growth that would put a 3D printer in every home. As it says on the front page: “RepRap is humanity’s first general-purpose self-replicating manufacturing machine.” Well, kinda.

Just to set the record straight, I love the RepRap project. My hackerspace put our funds together to build one of the first few Darwins in the US: Zach “Hoeken” came down and delivered the cut-acrylic pieces in person. I have, sitting on my desk, a Prusa Mendel with 3D parts printed by Joseph Prusa himself, and I spent a fantastic weekend with him and Kliment Yanev (author of Pronterface) putting it together. Most everyone I’ve met in the RepRap community has been awesome, giving, and talented. The overarching goal of RepRap — getting 3D printers in as many peoples’ hands as possible — is worthy.

But one foundational RepRap idea(l) is wrong, and unfortunately it’s in the name: replication. The original plan was that RepRap printers would print other printers and soon everyone on Earth would have one. In reality, an infinitesimal percentage of RepRap owners print other printers, and the cost of a mass-produced, commercial RepRap spinoff is much less than it would cost me to print you one and source the parts. Because of economies of scale, replicating 3D printers one at a time is just wasteful. Five years ago, this was a controversial stance in the community.

On the other hand, the openness of the RepRap community has fostered great advances in the state of the DIY 3D printing art. Printers haven’t reproduced like wildfire, but ideas and designs have. It’s time to look back on the ideal of literal replication and realize that the replication of designs, building methods, and the software that drives the RepRap project is its great success. It’s the Open Hardware, smarty! A corollary of this shift in thought is to use whatever materials are at hand that make experimentation with new designs as easy as possible, including embracing cheap mass-produced machines as a first step. The number of RepRaps may never grow exponentially, but the quality and number of RepRap designs can.

Continue reading “Getting It Right By Getting It Wrong: RepRap And The Evolution Of 3D Printing”