Generating video signals with a microcontroller or old CPU is hard if you haven’t noticed. If you’re driving even a simple NTSC or PAL display at one bit per pixel, you’re looking at a minimum of around 64kB of RAM being used as a frame buffer. Most microcontrollers don’t have this much RAM on the chip, and the AVR video builds we’ve seen either have terrible color or relatively low resolution.

Here’s something interesting that solves the memory problem and also generates analog video signals. Yes, such a chip exists, and apparently this has been in the works for a very long time. It’s the VLSI VS23s010C-L, and it has 131,072 bytes of SRAM and a video display controller that supports NTSC and PAL output.

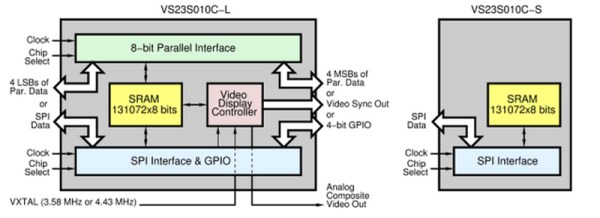

There are two chips in the family, one being an LQFP48 package, the other a tiny SMD 8-pin package. From what I can tell from the datasheets, the 8-pin version is only an SPI-based SRAM chip. The larger LQFP package is where the action is, with parallel and SPI interfaces to the memory, an input for the colorburst crystal, and composite video and sync out.

After looking at the datasheet (PDF), it looks like generating video with this chip is simply a matter of connecting an RCA jack, throwing a few commands to the chip over SPI, and pushing bits into the SRAM. That’s it. You’re not getting hardware acceleration, you’re going to have to draw everything pixel by pixel, but this looks like the easiest way to generate relatively high-resolution video with a single part.

Thanks [antibyte] for the tip on this one.