When you see the term cold fusion, you probably think about energy generation, but the Cold Metal Fusion Alliance is an industry group all about 3D printing metal using Selective Laser Sintering (SLS) printers. The technology promoted by Headmade Materials typically involves using a mix of metal and plastic powder. The resulting part is tougher than you might expect, allowing you to perform mechanical operations on it before it is oven-sintered to remove the plastic.

The key appears to be the patented powder, where each metal particle has a thin polymer coating. The low temperature of the laser in the SLS machine melts the polymer, binding the metal particles together. After printing, a chemical debinding system prepares the part — which takes twelve hours. Then, you need another twelve hours in the oven to get the actual metal part.

You might wonder why we are interested in this. After all, SLS printers are unusual — but not unheard of — in home labs. But we were looking at the latest offerings from Nexa3D and realized that the lasers in their low-end machines are not far from the lasers we have in our shops today. The QLS230, for example, operates at 30 watts. There’s plenty of people reading this that have cutters in that range or beyond out in the garage or basement.

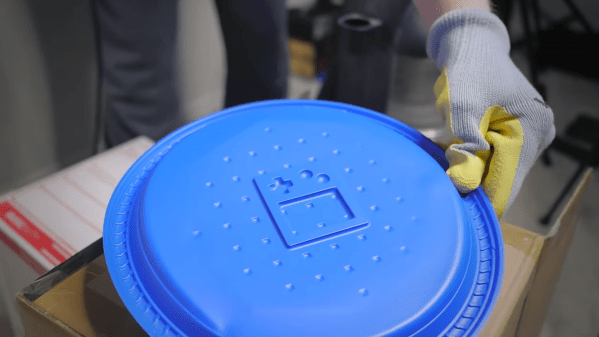

We aren’t sure what a hobby setup would look like for the debinding and the oven steps, but it can’t be that hard. Maybe it is time to look at homebrew SLS printers again. Of course, the powder isn’t cheap and is probably hard to replace. We saw a 20 kg tub of it for the low price of €5,000. On the other hand, that’s a lot of powder, and it looks like whatever doesn’t go into your part can be reused so the price isn’t as bad as it sounds. We’d love to see someone get some of this and try it with a hacked printer.

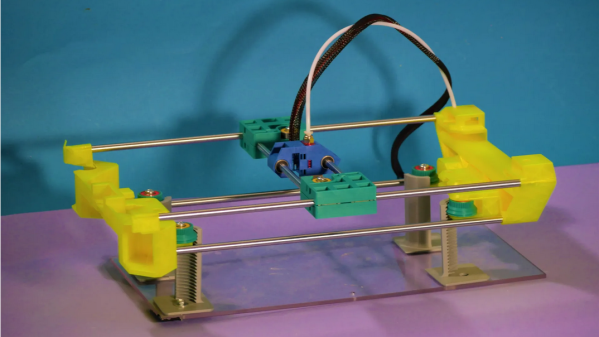

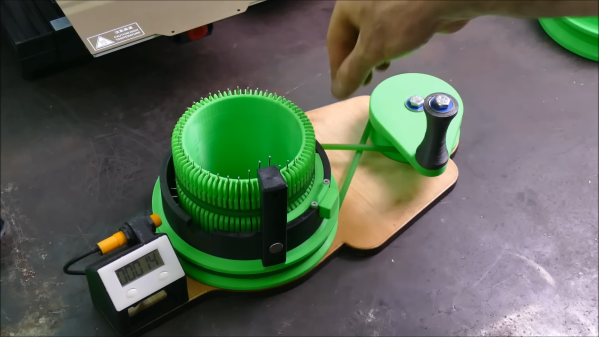

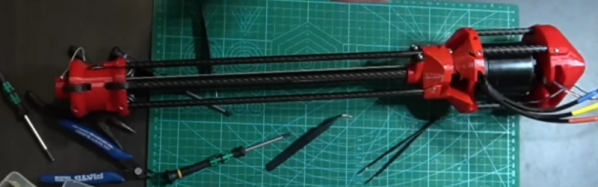

We have seen homebrew SLS printers. There’s also OpenSLS that, coincidentally, uses a laser cutter. It wouldn’t be cheap or easy, but being able to turn out metal parts in your garage would be quite the payoff. Be sure to keep us posted on your progress.