[Louise Katzovitz] has created a light-up jacket in the style of the jacket worn by Michael Jackson in the 1983 music video for “Thriller”. [Louise Katzovitz]’s Thriller jacket is the perfect example of combining sewing hacks and electronic hacks to make an awesome, wearable jacket.

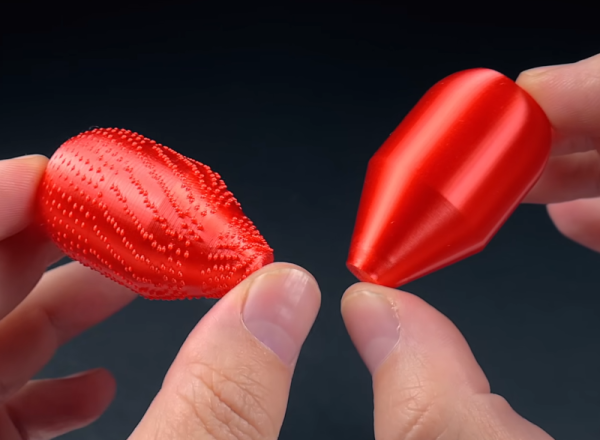

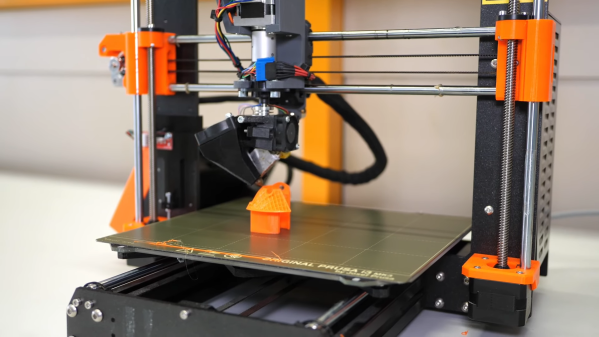

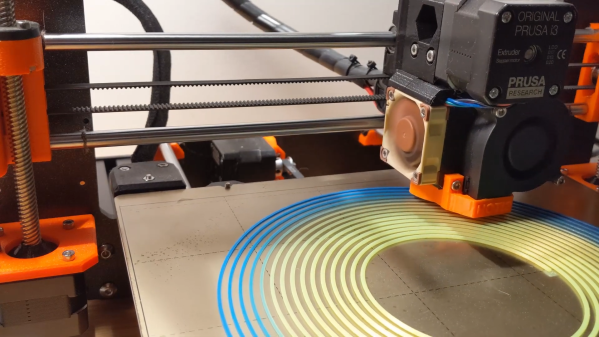

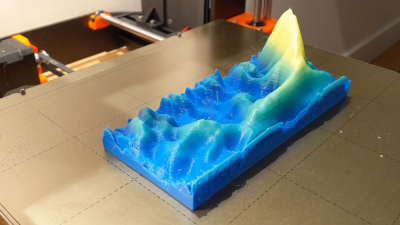

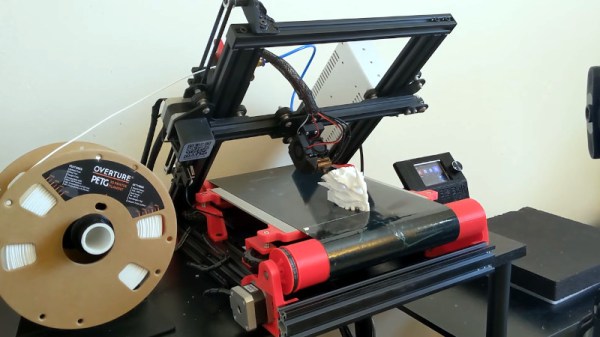

A bomber jacket was used as the base form to layer on the sequins and LED strips. Instead of bands of metal studs, [Louise] used WS2812B 60 pixels/m LED strips. 3D-printed transparent PLA “gems” were placed on top of the LEDs to mimic the form of the metal studs in the original jacket and provide diffusion for the underlying LEDs.

Each LED strip was laid out on a piece of vinyl strip. Then, a top layer of vinyl was cut to allow each of the LEDs to poke through, with the 3D printed gems super-glued on top. The assembled LED bands are attached to the jacket by Velcro with the wiring fed behind the lining material, which can be removed easily via small hooks. The whole thing is driven by an Arduino Nano and a 5 V power bank.

With the details and process worked out, [Louise] even made a tiny version of the jacket for her dog. We’ve featured LED wearables and fashion before and [Louise]’s jacket is a great addition. These projects are perfect for anyone who wants to wow their friends this upcoming Halloween season. Video after the break!