[Mike Gardi] credits his professional successes in the world of software development on the fact that he had access to logic-based educational games of a sort that simply don’t exist anymore. Back in the 1960s, kids who were interested in electronics or the burgeoning world of computers couldn’t just pick up a microcontroller or Raspberry Pi. They had to build their “computers” themselves from a kit.

One of those kits was the GENIus Almost-automatic Computer (GENIAC), a product which today is rare enough to essentially be unobtainable. Using images and documentation he was able to collect online, [Mike] not only managed to create a functioning replica of the GENIAC, but he even took the liberty of fixing some of the issues with the original 60-odd year old design.

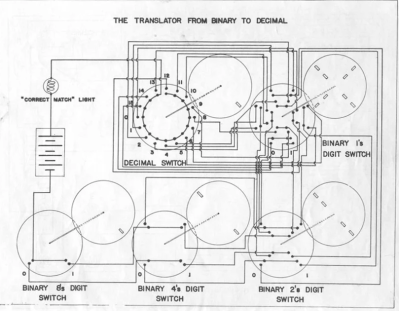

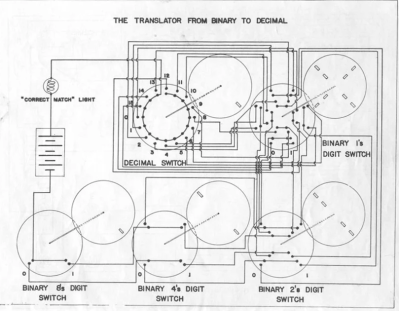

Fundamentally, the GENIAC is composed of rotary switches which feed into each other to perform rudimentary logical functions. With banks of incandescent bulbs serving as the output, users could watch how placing the switches in different positions would influence the result.

Fundamentally, the GENIAC is composed of rotary switches which feed into each other to perform rudimentary logical functions. With banks of incandescent bulbs serving as the output, users could watch how placing the switches in different positions would influence the result.

This might seem a little silly to modern audiences, but thanks to a well written manual that featured a collection of compelling projects, the GENIAC managed to get a lot of mileage out of a couple light bulbs and some wire. In fact, [Mike] says that the GENIAC is often considered one of the first examples of an interactive electronic narrative, as the carefully crafted stories from the manual allowed players to go on virtual adventures long before the average kid had ever heard of a “video game”. A video about how one of these stories, “The Uranium Shipment and the Space Pirates“, can be seen after the break. Even today it would be an interesting enough toy, but back in 1955 it would have been mind-blowing.

Construction of this replica will require access to a laser cutter so you can approximate the original’s drilled Masonite backing and rotors. From there, [Mike] has produced an array of 3D printable components which are attached to the board to serve as contacts, spacers, and various other pieces of bric-a-brac. Some of the parts he couldn’t find pictures of, so he was forced to come up with his own designs. But considering the finicky nature of the original, he thinks his printed parts may actually be better than what the toy shipped with.

If you like his work with GENIAC, be sure to check out the 3D printed replica of “The Amazing Dr. Nim” that [Mike] made last year, or his breathtaking recreation of the Minivac 601.

Continue reading “The GENIAC Lives Again” →