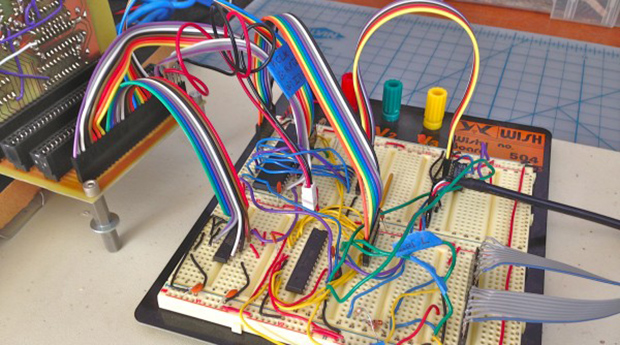

Can you spot the serial port in the pic above? You can probably see the potential pads, but how do you figure out which ones to connect to? [Craig] over at devttys0 put together an excellent tutorial on how to find serial ports. Using some extreme close-ups, [Craig] guides us through his thought process as he examines a board. He discusses some of the basics every hobbyist should know, such as how to make an educated guess about which ports are ground and VCC. He also explains the process to guessing the transmit/receive pins, although that is less straightforward.

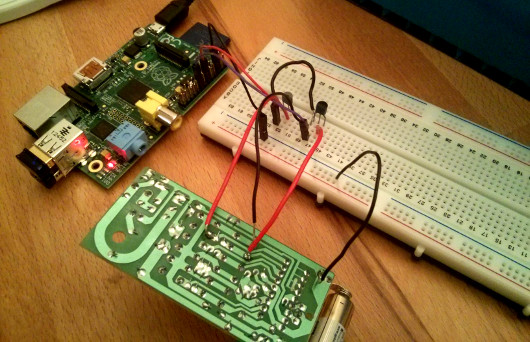

Once you’ve identified the pins, you need to actually communicate with the device. Although there’s no easy way to guess the data, parity, and stop bits except for using the standard 8N1 and hoping for the best, [Craig] simplifies the process a bit with some software that helps to quickly identify the baud rate. Hopefully you’ll share [Craig’s] good fortune if you reach this point, greeted by boot messages that allow you further access.